- Home

- Cruiser Yachts under 30'

- Albin Ballad

The Albin Ballad 30 Sailboat

The Albin Ballad sailboat was designed by Rolf Magnusson and manufactured by Albin Marine in Sweden throughout the years 1971 to 1981.

Published Specification for the Albin Ballad

- Keel & Rudder Configuration: Fin keel with a skeg-hung rudder. The lead ballast is encapsulated within the fibreglass keel.

- Hull Material: GRP (fibreglass), with the deck being a fibreglass-Divinicell sandwich.

- Length Overall (LOA)*: 9.14 m (29'11")

- Waterline Length (LWL)*: 6.88 m (22'7")

- Beam*: 2.95 m (9'8")

- Draft*: 1.55 m (5'1")

- Rig Type: Masthead Sloop

- Displacement*: 3,300 kg (7,276 lbs)

- Ballast*: 1,550 kg (3,417 lbs)

- Sail Area (main plus 100% foretriangle)*: Approximately 34.93 m² (375.94 ft²)

- Water Tank Capacity: Approximately 65 litres (17.2 US Gallons / 14.3 Imperial Gallons)

- Fuel Tank Capacity: Approximately 33 litres (8.7 US Gallons / 7.2 Imperial Gallons)

- Hull Speed: Approximately 6.38 knots

- Designer: Rolf Magnusson

- Builder: Albin Marine (Sweden)

- Year First Built: 1971

- Year Last Built: 1981 (production by Albin Marine), with some built until 1998 by other yards after moulds were acquired by the Ballad One-Design Association.

- Number Built: Approximately 1,500

* Used to derive the design ratios referred to later in this article - here's how they're calculated...

Options & Alternatives

The Albin Ballad was primarily designed and built as a masthead sloop with a fixed fin keel (1.55 m draft). There's no widespread indication of factory-offered alternative rig types (like fractional, cutter, or ketch), nor alternative deep or shallow draft options. The standard interior layout featured a saloon with two settee berths and two pilot berths, a small galley, chart table, heads compartment, and a V-berth forecabin. While owners may have customised their boats, multiple factory-offered layouts aren't typically noted.

The Albin Ballad remained a consistent design throughout its main production run. It drew heavily from Rolf Magnusson's successful "Joker" racing design, but no alternative "versions" with significant design departures were introduced. The Delta 31 replaced the Albin Ballad 30 in Albin Marine's product line in 1983. Later, the Ballad One-Design Association acquired the moulds, leading to a few more boats being built by different Swedish yards until 1998. These later builds likely incorporated minor material or component updates rather than fundamental design changes. Engine updates over the production run included Volvo Penta MD6A, MD6B, MD7A, MD7B, and later VP 2002 models.

Sail Areas & Rig Dimensions

Sail Areas & Rig Dimensions

Sail Areas & Rig DimensionsSail Areas

- Mainsail Area: 15.9 m² (171 ft²)

- 100% Foretriangle Area: 21.08 m² (226.87 ft²)

- Genoa (105%): 25.2 m² (271.25 ft²)

- Genoa (135%): 28 m² (301.4 ft²)

- Spinnaker Area: 70 m² (753 ft²)

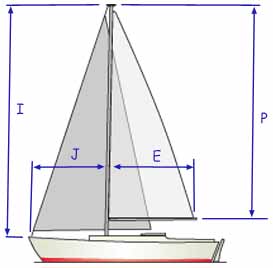

Rig Dimensions

- I: 11.30 m (37'0")

- J: 3.73 m (12'3")

- P: 9.75 m (32'0")

- E: 2.84 m (9'4")

Published Design Ratios

The Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

The key design ratios for the Albin Ballad are:

- Sail Area/Displacement Ratio (SA/D): 16.1 (based on 100% foretriangle); up to 18.71 (with 135% genoa)

- Ballast/Displacement Ratio (B/D): 47.0%

- Displacement/Length Ratio (D/L): 282

- Comfort Ratio: 22.1

- Capsize Screening Formula (CSF): 2.0

Theoretical Sailing Characteristics

The design ratios paint a picture of the Albin Ballad as a well-balanced cruiser-racer:

- Sail Area/Displacement Ratio (SA/D - 16.1 to 18.71): This indicates good performance potential. The Ballad has ample sail area to move well, particularly in light to moderate winds, classifying it as a capable performer.

- Ballast/Displacement Ratio (B/D - 47.0%): A high B/D suggests a stiff and powerful boat that stands up well to the wind, resisting excessive heel. This contributes to better performance to windward and a more comfortable motion at sea. The encapsulated lead fin keel enhances this stability.

- Displacement/Length Ratio (D/L - 282): Falling into the "heavy displacement" category, the Ballad is robustly built with significant volume. Heavy displacement boats generally offer a more comfortable ride in rough seas, are less affected by chop, and can carry stores effectively.

- Comfort Ratio (22.1): This suggests a moderately comfortable motion at sea, making it suitable for cruising.

- Capsize Screening Formula (CSF - 2.0): A value of 2.0 indicates good initial stability and resistance to capsize, suggesting the Albin Ballad is capable of handling offshore passages if properly equipped.

In essence, these ratios suggest the Albin Ballad is a relatively heavy and stiff boat that can manage its sail area effectively. It offers good performance in various conditions while providing a comfortable and seaworthy ride, making it suitable for both club racing and coastal or even offshore cruising.

But the Design Ratios are Not the Whole Story...

While design ratios offer a useful theoretical starting point for understanding a sailboat's characteristics, they have significant limitations:

Simplification and Generalisation: Ratios condense complex interactions into single numbers, providing a general idea without capturing the specific nuances of a design.

Lack of Shape and Distribution Detail:

- Ballast/Displacement Ratio: It doesn't account for the shape or location of the ballast. A deep lead bulb keel provides more righting moment than the same weight spread in a shallower, wider keel.

- Sail Area: Ratios often use simplified calculations (e.g., main + 100% foretriangle) and don't account for the actual shape, efficiency, or quality of the sails or rig.

- Hull Shape: The D/L ratio doesn't describe the hull's specific form – its entry, exit, wetted surface area, or how it performs at different speeds.

Static vs. Dynamic Performance: Ratios are largely static. They don't predict how a boat will behave dynamically in varying conditions, such as its actual upwind or downwind performance, which depend on factors like keel and rudder foil shapes, hull drag, and rig tuning.

Influence of Appendages: The efficiency and shape of crucial appendages like the keel and rudder, vital for steering, control, and lift, are not directly quantified by these broad ratios.

Wind and Sea Conditions: Ratios are averages. A boat might perform well in light air based on its SA/D but be overcanvassed in heavy winds. A "comfortable" boat might still be uncomfortable in specific wave patterns.

Crew Skill and Trim: Optimal performance relies heavily on skilled crew and proper sail trim, factors completely outside the scope of design ratios.

Engine and Propeller: For motorsailing or manoeuvring, the engine and propeller efficiency are crucial, but these are not covered by sailing design ratios.

Structural Integrity and Build Quality: Ratios offer no insight into the quality of construction, the strength of the hull, deck, or rigging.

Subjective Factors: Elements like "feel" on the helm, responsiveness, ease of handling, and overall motion comfort are subjective and not fully captured by numerical ratios.

In conclusion, while design ratios are valuable for general comparisons, they should never be the sole basis for evaluating a boat's actual sailing performance or suitability. A comprehensive understanding requires considering detailed hull lines, rig specifics, construction methods, and real-world sea trials.

More Specs & Key Performance Indicators for Popular Cruising Boats

Recent Articles

-

Sizing Your Yacht's 12v Domestic Battery Bank | Expert Cruising Guide

Mar 10, 26 07:01 PM

Learn how to accurately size your yacht's domestic battery bank for offshore passages. Calculate ampere-hour demand and manage energy efficiently. -

Allures 45.9 Review: Performance, Specs & Cruising Capability

Mar 07, 26 03:22 PM

An expert review of the Allures 45.9 sailboat. Explore technical specs, aluminium construction benefits, and how the lifting keel performs for blue-water cruising. -

Jeanneau Sun Legende 41 Review: Specs, Performance & Buying Advice

Mar 06, 26 12:26 PM

An expert review of the Doug Peterson-designed Jeanneau Sun Legende 41. Discover performance ratios, build quality details, and a buyer's checklist for this classic cruiser.