- Home

- Offshore Seamanship and Heavy Weather Tactics

- Tradewinds Sailing

Sailing the Tradewinds: Essential Tips for Optimising Route & Comfort

In a Nutshell...

Tradewinds sailing is the quintessential ocean passage experience, but it’s often more boisterous and tiring than the idyllic picture suggests. The key to a fast, comfortable downwind crossing lies in proactive rig management—specifically favouring a twin headsail rig over a heavily prevented mainsail—and a robust, energy-independent self-steering system. By planning your route to avoid the worst of the rolling and the season's severe weather, and implementing effective power generation, you can transform a relentless, tiring slog into an enjoyable, high-speed run toward your tropical destination.

Reefed-down in the tradewinds

Reefed-down in the tradewindsTable of Contents

- The Reality of Downwind Cruising

- Optimising the Downwind Rig: Stability & Safety

- Autosteering: The Essential Crew Member

- Keeping the Power On: Energy Generation

- Strategic Planning: Timing, Routes & Provisions

- Heavy Weather & Storm Management in the Trades

- Managing Mast Fatigue & Rig Tune Downwind

- Chafe Management & Rig Longevity

- Summing Up

- Frequently Asked Questions

The Reality of Downwind Cruising

That classic image of a yacht effortlessly gliding across a deep blue ocean, pushed by a balmy following wind, is largely accurate, but it rarely tells the full story. For an experienced ocean sailor, the reality of a long Tradewinds sailing passage—like the 3,000-mile run from the Canaries to the Caribbean—is one of constant rolling.

With the wind and swell directly astern, your boat's motion can be relentless. I've logged countless miles on these routes, and that six-second roll period you calculate quickly translates into fatigue. Rolling 14,400 times a day is a massive energy drain on both the crew and the boat structure. Getting the rig right isn't just about speed; it's about stability and sanity.

Tradewinds aren't confined to the Atlantic. They grace the Pacific on routes toward the South Pacific islands, and further south across the Atlantic from the Cape Verde Islands. The choice depends on your timeline and, more importantly, the seasonal weather window—which we'll cover later. A characteristic feature of these runs is the sudden, squall-driven wind shifts and torrential rain that bowls in from astern, demanding immediate and stress-free sail changes.

Optimising the Downwind Rig: Stability & Safety

My advice is to prioritise a rig that handles the inevitable line squalls gracefully without demanding difficult, drastic sail changes. Dealing with a fully-out main and a poled-out jib while rounding up in a squall to reef, only to bear away again, is a recipe for broken gear or, worse, injury.

The Twin Headsail Rig Advantage

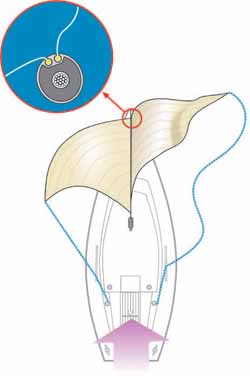

Ideally, both sails would be of similar size

Ideally, both sails would be of similar sizeFor me, the twin headsail rig is the gold standard for Tradewinds sailing. It's inherently more stable, centres the effort lower and further forward, and eliminates the need for the mainsail and its cumbersome preventer.

Most modern cruising yachts come with a twin luff-groove headsail furling system, which is ideal. However, setting two sails simultaneously can be awkward. Here is a better, more flexible approach that I've used successfully:

- Temporary Halyard Block: Attach a high-quality block to the head shackle of the top swivel. Reeve a Spectra (Dyneema) halyard through this block, tying off both ends to the tack swivel on the furling drum. This creates a dedicated, external halyard for the second headsail, allowing you to use your primary sail as normal.

- Hoisting the Second Sail: When hoisting the second headsail, ensure the spare luff groove is facing forward. If it isn't, a controlled gybe will correct the foil's orientation. Trying to hoist with the groove facing aft guarantees the sail will wrap around the foil, leading to significant friction and a failed hoist.

- Squall Management: A key benefit is that the sails can be furled simultaneously (or sequentially, depending on your drum setup) when a squall hits, offering an immediate reduction in sail area without needing to leave the cockpit.

Make sure the luff groove is facing foward when hoisting the second sail

Make sure the luff groove is facing foward when hoisting the second sailFor maximum stability, the twin sails should be of similar size and supported by similar length poles—often a dedicated spinnaker pole and a whisker pole. Relying on the boom as a substitute pole is a poor compromise that adds unnecessary weight and stress to the rig.

Alternative Downwind Sails

While the twin headsail is the workhorse, having alternatives is sensible:

- Asymmetric Spinnaker/Cruising Chute: These offer a substantial boost in speed in lighter air or when the wind angle is just slightly off dead astern (broad reaching).

- The Snuffer/Sock: A "sock" or snuffer is a non-negotiable piece of kit for any large off-wind sail. It allows for quick, controlled setting and dousing, which is crucial when a black line of squalls appears rapidly on the horizon.

Autosteering: The Essential Crew Member

No one wants to hand-steer for a week, let alone a three-week ocean crossing. Reliable self-steering is vital for safety, rest, and energy management.

Windvane Self-Steering

Windvanes are brilliant on a beat or a close reach, but they often struggle downwind in the trades. With a true wind of 12 knots and a boat speed of 6 knots, the apparent wind over the vane is only 6 knots. That’s at the effective lower limit of most systems. While they can perform, they require perfect sail balance and constant monitoring, which defeats the purpose. Don't rely too heavily on them as your sole primary system on a pure downwind run.

Electronic Autopilot

For most modern sailors, the electronic autopilot is the primary driver. It works regardless of wind angle and is incredibly precise. The obvious trade-off is its voracious appetite for electricity. A powerful ram or drive unit can draw serious amperage, and that energy has to be replaced. This is why having a robust charging system is non-negotiable.

Sheet-to-Tiller Steering

I’m a big advocate for tillers on aft-cockpit cruising boats—they offer superior feel and require less maintenance than wheel systems, but that’s an argument for another day! The tiller is essential for a tried-and-tested back-up: sheet-to-tiller steering.

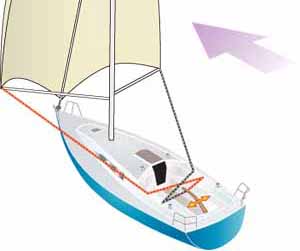

Setting up a sheet-to-tiller steering system with a twin headsail rig

Setting up a sheet-to-tiller steering system with a twin headsail rigWith the twin headsail rig set, you can cross the sheets in the cockpit through a pair of blocks and tie them to the tiller. This forms a self-balancing system. The key is in the fine-tuning:

"It takes fiddling—one eye on the compass, one on the windex, and a sheet in each hand—but once you find the perfect attachment point for a given wind angle, this setup will hold a downwind course for hours with almost no fuss. It’s a wonderful, power-free failsafe when your primary systems have thrown in the towel."

While it's unlikely to be your primary method, it's an indispensable skill to have when all else fails.

Keeping the Power On: Energy Generation

The demands of an electronic autopilot, navigation systems, refrigeration, and communication gear mean power management is critical. Running the engine for battery charging is noisy, burns fuel, and is completely against the spirit of sailing.

Wind & Solar: Tropical Twins

- Solar Panels: In the tropics, the sun is high and intense. Solar panels perform at their absolute best here. Modern flexible and semi-flexible panels, strategically mounted to avoid shadow, can provide a substantial daily charge. However, in the tropics, the nights are long, and they stop working entirely at sunset.

- Wind Chargers: Like windvanes, their output is a direct function of apparent wind speed. On a downwind run, a 15-knot true wind might only be 8 knots apparent, severely limiting output. Don’t expect miracles from your wind generator on a dead-downwind passage.

Water-Based Generators: The Amp Machines

| Generator Type | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Towed Generators | High, consistent output 24/7; excellent for power-hungry yachts. | Reduces boat speed by up to half a knot (12 miles/day); risk of tangles with fishing lines; a known target for curious fish. |

| Propeller Shaft Generators | Quiet; convenient; excellent output. | Creates significant drag when the propeller is free-wheeling (far more than a towed unit); will not work with common drag-reducing propellers (folding & feathering). |

For a serious ocean passage, a combination of solar and a towed generator usually offers the best balance of reliable, low-drag, 24-hour power.

Strategic Planning: Timing, Routes & Provisions

Timing & Weather Patterns

The notion of the "reliable" tradewind can be misleading. You must plan your departure to avoid two major threats:

- Hurricane Season: For the North Atlantic, the sailing window is typically late autumn through to late spring. Leaving too early or too late is inviting danger.

- The ITCZ: The Intertropical Convergence Zone (the Doldrums) is a band of unstable weather that must be crossed or skirted. Getting stuck in or dealing with the extreme weather generated here can be miserable and potentially dangerous.

GRIB files are your most valuable asset. Used via satellite communication (Iridium GO! or Starlink), they provide the necessary granularity on wind and wave predictions to let you find the most comfortable and fastest path.

Provisioning for the Heat

Weeks at sea in tropical heat demand a different provisioning mindset. Forget anything fresh that won't last. Focus on:

- Non-Perishable Staples: Vacuum-packed rice, pasta, dried beans, tinned goods, and long-life milk.

- Hydration: A reliable watermaker is a massive comfort and safety feature. Supplement this with an effective rainwater catchment system rigged off the mainsail boom or bimini.

- Crew Morale & Health: Don't underestimate the psychological lift of good food. Stock up on long-lasting, vitamin-rich produce (cabbages, potatoes, citrus) and comfort items (coffee, chocolate).

Crew Management

Long, rolling downwind passages are more tiring than people expect. Fatigue management is paramount:

- Clear Watch Schedules: Even on a short-handed boat, formal schedules are essential to ensure adequate, uninterrupted rest.

- Task Rotation: Rotate non-sailing duties to keep things interesting and prevent boredom.

- Maintaining Morale: Keep the onboard atmosphere positive. Good food, shared storytelling, and a sense of routine make a monumental difference to endurance.

Maintaining discipline, setting clear protocols, and managing the inevitable fatigue of a long passage are the cornerstones of safe offshore operations, reflecting many of the crucial elements covered in our comprehensive guide on Mastering Offshore Seamanship & Safety: Protocols, Heavy Weather & Crew Tactics.

Heavy Weather & Storm Management in the Trades

While the trades are generally benign, they are also prone to extremely rapid-onset, violent weather, which demands respect and a pre-planned strategy.

A line squall often means a wind shift, an increase of 20 knots of wind, and blinding rain, all in a matter of minutes. More serious is the possibility of encountering a sustained gale or the fringes of a developing tropical system—especially if you're delayed or have entered the danger period.

Pre-emptive Rigging & Preparation

- Reef Early & Often: If you see an ominous black cloud line, furl the twin headsails immediately. Don’t wait until the first gust hits.

- Secure the Helm: If the auto-pilot or vane is struggling in a heavy quartering sea, consider using a tiller pilot on standby to handle the worst of the steering, or even momentarily hand-steering to prevent an unintentional gybe.

- Heaving-To vs. Running Off: In the tradewinds, the wind and sea are typically following, which favours running off under bare poles or a tiny scrap of headsail in a true gale. Trying to heave-to and face the large, quartering swell is likely to induce severe rolling and structural strain. The priority is to maintain control and avoid broaching.

- Hatch & Port Security: Before the squall arrives, ensure all hatches, ports, and lockers are fully dogged down. The volume of water that comes aboard during a tropical downpour can be astonishing.

- Minimise Friction: On a heavy run, chafe is the number one enemy. Constantly check sheets, guys, and fairleads, particularly for the poled-out lines. A small piece of sun-rotted stitching can give way at the worst possible time.

As something of an old salt, my rule is simple: if you think you might need to reduce sail, you already should have. The time to implement your storm strategy is when the sun is shining and the crew is rested, not when you’re being hammered by a 40-knot line squall at 03:00.

Managing Mast Fatigue & Rig Tune Downwind

The inherent rolling motion of a yacht running dead downwind creates a severe, cyclical load that can rapidly accelerate fatigue in your standing rigging and mast structure. Unlike sailing upwind where shrouds and forestays are highly loaded and relatively static, downwind the mast is constantly being hammered sideways.

Preventative Rigging Checks

- Check the Lowers: Make sure your lower shrouds (V1s and D1s/D2s) are appropriately tensioned. They are the primary defence against the mast pumping sideways, which contributes directly to fatigue. A slightly tighter tune than normal can mitigate excessive side-to-side movement.

- Pin Checks: The constant vibration and motion on a long run are notorious for causing cotter pins and split rings to work loose or fail. A daily check of clevis pins, especially at the chainplates and mast base, is non-negotiable. Missing a pin is the fastest way to lose a rig.

- Avoid Over-Tensioning: While you want to limit side-to-side movement, be wary of over-tensioning the mast when sailing downwind. This can simply shift the destructive forces to the compression post and mast step, especially if the rig is heavily checked by solid boom vangs or excessive preventer tension. It’s a delicate balance best maintained by having a stable sail plan (i.e., the twin headsails).

Chafe Management & Rig Longevity

The number one enemy of a long-distance downwind sailor is chafe. The constant, low-amplitude movement of the boat will, over time, saw through even the thickest lines and sails. Proactive chafe prevention isn't maintenance; it is a fundamental safety protocol.

High-Risk Chafe Points

- Headsail Sheets: Where they pass through the fairleads, blocks, or where they wrap around the end of the whisker poles.

- Spreader Tips: Where the mainsail (even if partially up to dampen rolling) or the clew of a full-size headsail contacts the stainless tips.

- Running Rigging Exits: Where halyards exit the mast or running backstays pass over the deck.

- Preventer & Pole Lines: The constant, high load on the boom preventer and the pole up-haul/down-haul lines makes them prone to wear where they pass over turning blocks or hard edges.

Prevention Tactics

- Chafe Gear is Sacrificial: Always deploy sacrificial chafe gear. This can range from purpose-made sleeves (Velcro or tubular webbing) to simple leather patches, PVC tubing slipped over shrouds, or even fire hose sections on mooring bridles. The goal is to let the protection wear out, not the line underneath.

- Rigging Inspection Routine: Institute a rigorous daily check. On watch, the sailor’s job isn't just to look at the compass; it’s to walk the deck and physically feel for friction points. Where sheets pass over the toe rail, apply self-amalgamating tape or robust patch material.

- Moving the Load: For high-load lines that run through clutches or mast sheaves (like the main halyard), move the line slightly every few days. This spreads the point of wear along a greater length of the line, preventing concentrated damage in one spot.

- Sail Protection: Ensure your mainsail has spreader patches applied to both sides where it contacts the tips, and check these patches regularly for wear.

Summing Up

Successful Tradewinds sailing boils down to mitigating relentless motion and managing your power supply. By moving away from a traditional boom-and-main setup toward a twin headsail rig, you create a far more stable platform that shrugs off squalls and eliminates the anxiety of a runaway gybe. This stability, coupled with a robust, energy-independent autopilot system—fed by a combination of solar and a hydro-generator—and constant vigilance against chafe and rig fatigue, will have cracked the code for a comfortable, fast, and memorable offshore passage. The trades are a gift to the ocean sailor, but only if you respect their power and plan your setup meticulously.

This article was written by Dick McClary, RYA Yachtmaster and author of the RYA publications 'Offshore Sailing' and 'Fishing Afloat', member of The Yachting Journalists Association (YJA), and erstwhile member of the Ocean Cruising Club (OCC).

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the best time of year for a North Atlantic tradewinds passage?

What is the best time of year for a North Atlantic tradewinds passage?

The prime window for a comfortable, safe North Atlantic crossing (Canaries to Caribbean) is typically from late November to March. This avoids the worst of the Atlantic hurricane season, which officially runs from 1st June to 30th November.

How do I prevent my boat from rolling excessively downwind?

How do I prevent my boat from rolling excessively downwind?

Excessive rolling is caused by swell on the quarter and lack of sail stability. The best remedies are to run a twin headsail rig (or a main with minimal sail area) and to alter course slightly—even 5 or 10 degrees off dead downwind—to put the swell slightly off the beam, which can dramatically smooth out the motion.

Should I use a folding or feathering propeller on a tradewinds passage?

Should I use a folding or feathering propeller on a tradewinds passage?

Yes, absolutely. A folding or feathering propeller is essential to minimise drag and maximise boat speed under sail. However, remember that if you have either of these, a propeller shaft generator will not be able to function, so you’ll need to rely on solar and towed hydro-generators for your power.

What is the main danger of a line squall when running downwind?

What is the main danger of a line squall when running downwind?

The main danger is an uncontrolled gybe followed by a sudden, intense increase in wind speed that can break spars or snap rigging. The intense rain and poor visibility that accompany the squall also pose a risk of collision with debris or unlit vessels.

How much faster is a twin headsail rig than a main & jib?

How much faster is a twin headsail rig than a main & jib?

A twin headsail rig isn’t necessarily faster in terms of raw speed potential compared to a well-set spinnaker, but it is significantly more stable and safer for continuous long-distance running. It offers higher average speeds over 24 hours because the boat requires far less helm input and the crew is less fatigued, allowing the yacht to maintain its optimal course.

Is it better to heave-to or run off in a tradewinds storm?

Is it better to heave-to or run off in a tradewinds storm?

In the deep ocean, with the large following swells typical of a tradewinds storm, it is generally safer to run off under minimal sail or bare poles. Attempting to heave-to can subject the boat to severe, sudden rolling as large quartering seas pass under the stern, increasing the risk of structural damage or broaching.

Recent Articles

-

Beneteau Oceanis 331 Clipper Review: Specs, Performance & Ratios

Feb 04, 26 07:25 PM

A comprehensive review of the Beneteau Oceanis 331 Clipper sailboat. We analyse design ratios, interior layout, and performance for prospective cruising owners. -

Self-Tacking Headsails: Track Systems vs Hoyt Jib Booms

Feb 03, 26 06:26 AM

Master the mechanics of self-tacking headsails. We compare traditional club-footed rigs, curved tracks, and the superior Hoyt Jib Boom for offshore sailing. -

Catalina 42 mk1 Review: Specs, Performance & Cruising Analysis

Feb 01, 26 06:35 AM

An in-depth review of the Catalina 42 mk1 sailboat. Explore technical specifications, design ratios, and practical cruising characteristics for this iconic cruiser.