- Home

- Cruising Sailboats

- Heavy Displacement Hulls

Heavy Displacement Hulls & Light: The Best Choice?

In a Nutshell...

Choosing between heavy displacement hulls and lighter designs for offshore cruising is a trade-off between comfort, speed, and handling. Heavy designs (high Displacement/Length Ratio or D/L) offer a sedate, comfortable motion (often with a high Comfort Ratio) and exceptional load-carrying capacity, but they are sluggish in light air and a nightmare for close-quarters manoeuvring. Lighter, modern designs (low D/L) deliver brisk performance and easier handling, though the ride can be livelier, and their carrying capacity is more sensitive to payload. For serious, long-term live-aboard offshore work, a moderate displacement hull often provides the best balance of comfort, performance, and seakeeping, a vital characteristic of the essential features of all good cruising sailboats.

With a Displacement/Length Ratio of 229, this Contest 44 is a fine example of a moderate displacement cruising boat

With a Displacement/Length Ratio of 229, this Contest 44 is a fine example of a moderate displacement cruising boatTable of Contents

- Understanding the Displacement/Length Ratio

- Heavy & Ultra-Heavy Displacement Hulls: The Tried & Tested

- The Sailor's Comfort Metric: Displacement & The Comfort Ratio

- Moderate Displacement Hulls: The Cruising Sweet Spot

- Light & Ultra-Light Displacement Hulls: Speed & Excitement

- The Effect on Rig & Sail Handling: Powering Heavy Displacement Hulls

- Construction & Material: The Weight-Bearing Factor

- Summing Up

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Understanding the Displacement/Length Ratio

When you're trying to figure out what makes a boat behave the way it does at sea, the Displacement/Length Ratio (D/L) is the single most influential metric. It’s what tells you, in simple terms, how much boat you're trying to push through the water relative to its length at the waterline. For a complete technical breakdown of this and other metrics that govern a sailboat's performance, see our article, Understanding Boat Performance & Design Ratios. This ratio has a consequential influence on a sailboat's stability, performance, and, crucially, your comfort when you're days from shore.

In the early days of cruising, heavy displacement hull forms were practically the only choice for long-distance offshore work, simply because the lightweight materials for hulls, spars, rigging, and all the associated fittings and equipment just weren't available. These days, though, with the advent of exotic composite laminates and modern fittings, super-strong and ultra-light displacement hull forms are regularly seen crossing the world’s oceans.

But don't go thinking the argument is settled! There are still plenty of experienced sailors who favour the easy motion of the older, heavier designs for offshore cruising, happily conceding the extra days spent at sea for the benefit of increased comfort in a seaway.

Here’s a quick look at how the D/L ratio is typically categorised:

| D/L Ratio | Displacement Type | Typical Cruising Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Under 90 | Ultra-Light | Performance-focused, planing potential, high price, lively motion. |

| 90 to 180 | Light | Brisk performance, good off-wind speed, sensitive to loading, easy handling. |

| 180 to 270 | Moderate | Best compromise, adequate speed, comfortable motion, good balance & stability. |

| 270 to 360 | Heavy | Sedate motion, excellent load-carrying, sluggish in light air, stable. |

| 360 & over | Ultra-Heavy | Traditionalists' choice, supremely comfortable in a blow, very slow, poor manoeuvring. |

Heavy & Ultra-Heavy Displacement Hulls: The Tried & Tested

With D/L ratios of 270 and over, these vessels are the traditional workhorses of the cruising world. For passionate cruising traditionalists, the Ultra-Heavy type (360 plus) is often de rigueur.

These heavier sailboats almost always feature a full (or long) keel. This configuration brings some fantastic benefits, along with some significant limitations, especially for the modern cruiser.

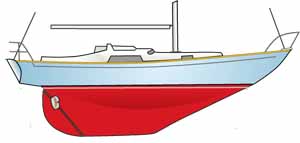

Underwater profile of a heavy-displacement long-keel sailboat

Underwater profile of a heavy-displacement long-keel sailboatThe Reality of a Long-Keeler

In light winds, a boat of this type will sail incredibly slowly—if at all—due to the massive drag caused by its high wetted area and the sheer power required to shift its weight. In my experience, a true heavy-displacement boat is only just getting into its stride when other more moderate types are taking in reefs.

I cut my cruising teeth on a craft of this type, a Nicholson 32 Mk10 ('Jalingo II') with a D/L ratio of 394. The long keel kept her tracking as if on rails; her directional stability was superb. Her motion underway was sedate, about as comfortable as you could get for a boat of that size. Her vee'd forward sections gave a soft ride, although she did show a tendency to bury her bows, making her a little wet on occasion.

"Jalingo II", a Nicholson 32 Mk10 was my first real long-distance sailboat. She was the epitome of an ultra-heavy long keel cruiser.

"Jalingo II", a Nicholson 32 Mk10 was my first real long-distance sailboat. She was the epitome of an ultra-heavy long keel cruiser.However, that enthusiasm for her seakeeping largely evaporated during close-quarters manoeuvring. She was a nightmare in a marina. Going astern with any degree of directional certainty was well-nigh impossible. You had to maintain plenty of way on to get her through the wind when a tack was called for. Furthermore, the ‘barn door’ proportions of their unbalanced rudders mean they are often quite heavy on the helm at all times.

The Heavy Advantage

The benefits, though, are compelling for the serious ocean sailor:

- Comfort: Their weight and deep V-sections provide a gentle, sedate motion that is less tiring for a crew on a long passage.

- Safety: The protected propeller and rudder and relatively shallow draft mean these boats will take the ground well and should breeze over floating ropes and nets without problem.

- Load Carrying: The high load carrying capacity is greatly appreciated by live-aboard sailors. You can stock up for months without the boat’s performance being drastically affected.

This combination of attributes makes the heavy-displacement boat best suited for those with ambitions to spend much of their time offshore in remote areas of the world. For those of us more inclined to spend our time island hopping in the Caribbean and Mediterranean, their sluggish performance might make them less attractive.

In the 'heavy' rather than 'ultra-heavy' displacement category, this Tayana 37 has a Displacement/Length Ratio of 337.

In the 'heavy' rather than 'ultra-heavy' displacement category, this Tayana 37 has a Displacement/Length Ratio of 337.To illustrate the impact of gear on performance, let’s look at the "Load-Carrying Penalty." It’s one of the most sobering realities for anyone transitioning from a weekend racer to a long-term cruiser.

The 500kg Litmus Test

When you add half a tonne of stores—water, fuel, ground tackle, and tinned goods—the physics of the hull changes. However, the severity of that change depends entirely on the boat's starting displacement.

| Metric | 7.6m Light Cruiser (D/L 200) | 12m Heavy Cruiser (D/L 200) |

|---|---|---|

| Empty D/L Ratio | 200 | 200 |

| Added Load | 500 kg | 500 kg |

| New D/L Ratio | ~242 | ~210 |

| Performance Impact | Severe: Significant increase in wetted surface area; the boat becomes sluggish and loses its ability to plane or move in light airs. | Negligible: The hull sits slightly lower, but the power-to-weight ratio remains largely intact. |

Why This Happens

A lighter, smaller hull has less "reserve buoyancy" in its narrow or flat sections compared to a larger or heavier hull. On a light-displacement boat, that 500kg might sink the boot-top by several inches, radically increasing drag and turning a "lively" sailor into a "lethargic" one.

For the heavy-displacement vessel, designed from the keel up to carry mass, that same load is a drop in the ocean. This is why the traditional "blue-water" choice remains heavy: it allows you to be self-sufficient without sacrificing the very seakeeping qualities you bought the boat for in the first place.

The Sailor's Comfort Metric: Displacement & The Comfort Ratio

While we've discussed the qualitative feeling of a boat's motion, the Motion Comfort Ratio (CR), developed by naval architect Ted Brewer, gives us a quantitative figure. It provides a numerical estimate of how comfortable a boat will be for the crew when subjected to waves.

The underlying principle is that greater displacement (weight) dampens the motion, while increased waterline length and beam can quicken the motion. As an experienced ocean sailor, I can tell you that this ratio is often a truer reflection of crew fatigue than speed alone. For serious offshore cruising, aiming for a CR of 30 or higher is a sound starting point to ensure a comfortable passage.

| Comfort Ratio (CR) | Cruising Implication |

|---|---|

| Below 20 | Light and very lively; generally confined to coastal or day sailing. |

| 20 – 30 | Coastal cruiser; capable of offshore work but can be tiring on long passages. |

| 30 – 40 | Moderate to heavy bluewater cruiser; excellent balance of comfort and speed. |

| 40 & over | Very comfortable, slow motion; supremely stable in a seaway. |

Moderate Displacement Hulls: The Cruising Sweet Spot

Moderate displacement sailboats (D/L ratio of 180 to 270) represent a natural, evolutionary development of the heavy displacement types. Typically, they feature a moderate length fin keel and a separate rudder, which is either transom hung or supported on a skeg.

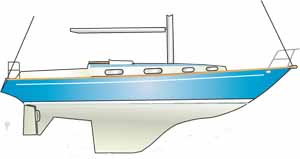

Underwater profile of a medium displacement fin-and-skeg sailboat

Underwater profile of a medium displacement fin-and-skeg sailboatWith a D/L ratio often around 240 to 300, this type remains a firm favourite with many long-distance cruisers. Why? They strike a genuine balance.

- Manoeuvrability: Performance, whilst not of the 'ocean greyhound' nature, is perfectly adequate in most conditions. Owing to the separation of the keel and rudder, manoeuvrability under both power and sail is vastly improved compared to a long-keeler.

- Handling: For a given Sail Area/Displacement ratio, the sail area required will be less than for the heavy type, making her easier to handle for a small crew.

- Construction: On GRP boats, the fin keel may be part of the hull moulding with its ballast encapsulated within. This avoids the need for keel bolts and the associated corrosion and security issues often linked with external ballast.

Directional stability and balance are dependent on the quality of the design, and there's no reason why both shouldn't be excellent, giving the crew confidence and making the boat easy to steer on passage. The blend of speed, stability, and handling that a moderate displacement hull offers is, in many ways, the clearest example of all the characteristics that define the Essential Features of All Good Cruising Sailboats.

Light & Ultra-Light Displacement Hulls: Speed & Excitement

Driven partially by the need for economy in a competitive market—lighter means less material—and an increasing demand for better performance, more and more modern production yachts are falling into the Light Displacement (90 to 180) category. These are often dubbed 'cruiser/racers'.

Typically with a D/L ratio around 200 and below, they'll sport a medium aspect ratio fin keel and a spade rudder. The underwater shape is dinghy-like, with minimal overhangs to maximise waterline length.

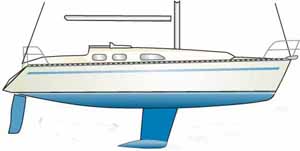

Underwater profile of a light displacement fin keel and spade rudder sailboat

Underwater profile of a light displacement fin keel and spade rudder sailboatLife Aboard a Light Hull

A lot of ballast is simply not an option for a light displacement boat, as so much of its stability is gained through increased beam. This means that when excessively heeled, the asymmetry of the immersed hull sections coupled with the broad beam carried well aft can make them hard on the helm.

Performance will be brisk in nearly all conditions, especially off the wind, when hull speed may well be exceeded. They are a delight to sail, pointing high and tacking through the wind with ease—passage times won’t be disappointing. The trick is to reef these boats early and sail them fairly flat. Sailing hard on the wind in vigorous conditions will be less comfortable than in a heavier craft; the flatter forward sections can tend to pound, and the ride is likely to be on the lively side.

Manoeuvrability under power, both ahead and astern, is usually good. Except, that is, when at low speed in a crosswind. I learned this the hard way with Alacazam (our self-build wood-epoxy sailboat) motoring out of a marina berth in Portugal. The wind blew the bow off as soon as I cleared the berth. The solution was simple, if embarrassing: let the bow blow around and motor out astern until there was enough room to turn! Lighter boats simply have less momentum to resist the windage.

36 feet of performance sailboat. This Wasa 30 has a D/L Ratio of just 91

36 feet of performance sailboat. This Wasa 30 has a D/L Ratio of just 91Load-Carrying Sensitivity

The load-carrying capacity of smaller light-displacement boats can be a real concern for cruisers. If you load, say, 680 kg of stores and equipment onto a 7.6m boat with a D/L Ratio of 200, its D/L ratio could jump to around 242. Load the same amount onto a 12m boat of the same D/L, and the ratio increases to only about 210. This is a much more performance-sapping penalty for the smaller, lighter boat, something the live-aboard sailor must carefully manage.

The Effect on Rig & Sail Handling: Powering Heavy Displacement Hulls

The choice of displacement has a cascading effect that moves from the hull right up to the top of the mast. The sheer mass you are trying to move dictates the size and complexity of the sail plan and, therefore, the necessary sail handling systems.

- Higher Loads, Bigger Gear: A heavy displacement boat requires a lot of sail area to overcome hull drag. This results in significantly higher loads on the rigging. To haul in a genoa sheet against the resistance of a heavy hull, much larger, more powerful winches are required. For the short-handed sailor on a heavy cruiser, electric or hydraulic winches are increasingly the norm to manage these forces.

- Divided Sail Plan: Heavy displacement boats often favour a cutter or ketch rig configuration. This splits the total required sail area into smaller, more manageable units. This is a practical advantage for cruising, as it makes reefing easier and provides a robust combination of sails to balance the boat when sailing short-handed in heavy weather.

- Simple Systems on Light Hulls: Lighter yachts require less power, and therefore have lower rig loads. This translates into simpler systems, often with smaller, yet still powerful, manual winches. Reefing the mainsail typically becomes the primary method of quickly depowering the boat, making the foresails smaller and easier to handle for a small crew.

While the D/L ratio defines the result of the design, the method of construction is what allows modern designers to achieve a low D/L without sacrificing strength.

Construction & Material: The Weight-Bearing Factor

Heavy and Ultra-Heavy boats often relied on thick, solid GRP laminates or heavy steel/ferrocement construction to achieve strength, which inherently created a high D/L ratio. This construction is robust, usually easy to repair with simple materials, and provides a quiet, well-insulated ride.

Modern Light and Moderate hulls, however, leverage advanced materials:

- Cored Composites: Using materials like balsa, foam, or Nomex as a core between thin layers of GRP/epoxy significantly increases stiffness and strength without adding much weight. This allows a modern racer/cruiser to be strong enough for the ocean yet maintain a light D/L ratio.

- Aluminium: This material is favoured for strong, relatively light, expedition-style cruising yachts. It provides excellent strength-to-weight and is highly durable.

A modern, light boat built with materials like a vacuum-bagged, foam-cored hull can be equally as strong as an older, heavy boat, but the feel and motion will be entirely different.

Summing Up

Optimum performance, handling, and comfort can't all be found at the same place on the sliding scale of displacement. The Displacement/Length Ratio is the crucial consideration for a prospective buyer. While boats at the heavy end will have a more comfortable, sedate motion—often quantifiable with a high Comfort Ratio—passage times will be slower and handling more cumbersome.

At the other end, the blistering performance of a ULDB (Ultra-Light Displacement Boat) will shake your fillings loose and demand constant trimming and sensitive weight management. Somewhere, between these two extremes, lies your ideal compromise—and for the vast majority of offshore cruisers, that sweet spot is Moderate Displacement, offering the speed to make good passages, the systems to be easily managed by a small crew, and the comfort to arrive without feeling utterly exhausted.

This article was written by Dick McClary, RYA Yachtmaster and author of the RYA publications 'Offshore Sailing' and 'Fishing Afloat', member of The Yachting Journalists Association (YJA), and erstwhile member of the Ocean Cruising Club (OCC).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Why are heavy displacement hulls better in a storm?

Why are heavy displacement hulls better in a storm?

Heavy displacement hulls have greater momentum and inertia, meaning they are less affected by individual waves. This results in a slower, more predictable, and easier motion in rough seas, which is less physically and mentally fatiguing for the crew over long periods.

Does a heavy displacement hull mean a safer boat?

Does a heavy displacement hull mean a safer boat?

Not necessarily. While they feel more 'solid' and are often built with thicker laminates, modern light displacement boats are engineered to be equally strong using high-tech materials and construction. The safety of any boat is ultimately determined by the quality of its design, build, and the preparation of the crew.

What is the ideal Displacement/Length Ratio for a live-aboard cruiser?

What is the ideal Displacement/Length Ratio for a live-aboard cruiser?

For most live-aboard sailors who value comfort, load-carrying, and a decent turn of speed, an ideal D/L ratio typically falls into the Moderate Displacement category, ranging from 180 to 270. This range provides a good balance for long-term cruising and stocking up on stores.

How does displacement affect the boat's motion?

How does displacement affect the boat's motion?

Lower displacement (lighter) boats tend to have a quicker, 'snappier' motion as they respond rapidly to waves, often leading to a livelier, or 'pounding,' ride. Higher displacement (heavier) boats absorb more of the wave energy, resulting in a more dampened, slower, and comfortable sedate motion. This is quantifiable using the Comfort Ratio.

Do heavy displacement boats require more crew to sail?

Do heavy displacement boats require more crew to sail?

Heavy displacement boats generate significantly higher loads on the sails and rigging than comparable light displacement boats. Therefore, they often require larger, more powerful winches (sometimes electric/hydraulic) and a more divided sail plan (like a cutter or ketch) to be sailed safely and efficiently by a short-handed crew.

What is the primary downside of an ultra-light displacement hull for cruising?

What is the primary downside of an ultra-light displacement hull for cruising?

The primary downside is the extreme sensitivity to added weight. An ultra-light boat can lose a significant percentage of its designed performance and trim from adding stores, fuel, and equipment, which quickly degrades its speed and handling.

Recent Articles

-

Beneteau Oceanis 473 Review: Specs, Performance & Cruising Guide

Feb 20, 26 04:49 AM

An in-depth review of the Beneteau Oceanis 473. Discover technical specifications, design ratios, and why this Groupe Finot design remains a top offshore cruising choice. -

Luders 36 Review: Specs, Performance Ratios & Cruising Guide

Feb 17, 26 06:20 PM

An in-depth expert review of the Luders 36 sailboat. Explore technical specifications, design ratios, and the offshore cruising capabilities of this classic Bill Luders design. -

Deck-stepped vs. Keel-stepped mast: An Offshore Engineering Guide

Feb 16, 26 07:59 AM

Comparing deck-stepped vs. keel-stepped mast systems. We analyze the propped cantilever effect, structural loads, and maintenance for offshore sailors.