- Home

- Sails

A Guide to Sailboat Sails: Powering Your Passage

In a Nutshell....

Sailboat sails are the engine of any sailing vessel, translating the wind's energy into forward motion. To get the most from your boat, you've got to understand how sails work, the distinct types and materials available, and the best practices for their use and care. For cruising sailors, the choice of durable Dacron and user-friendly roller-furling systems often balances performance with reliability and ease of handling. High-performance racing sails, on the other hand, use advanced, low-stretch materials like carbon fiber to maintain their precise shape at all costs. This guide will give you a comprehensive overview of sailboat sails, helping you to choose, use, and maintain them for your specific sailing needs.

Table of Contents

- We know what they are but How Do They Work?

- What are the various Parts of a Sail called?

- How to Trim & Tune Your Sails for Maximum Performance

- How is a Sail's Area Calculated?

- What are the Best Materials & Constructions for Sailboat Sails?

- What are the Main Types of Sailboat Sails & Their Uses?

- Sail Care & Maintenance

- Sail Safety & Handling

- Sail Repair & Knowing When to Replace Your Sails

- What are the Pros & Cons of Roller Furling Sails?

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

We know what they are but How Do They Work?

If the wind is the fuel, then a sailboat's sails are the engine. They've got to be meticulously designed and constructed to efficiently capture the wind's energy and convert it to motive power. The fundamental principle is one of aerodynamics, creating both lift and drag.

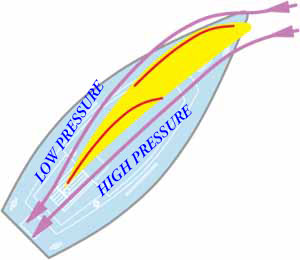

Airflow around the sails when beating to windward

Airflow around the sails when beating to windwardFor upwind sailing, or "windward work," sails act a lot like an aircraft's wing. The curved shape of the sail forces air to travel faster over the convex (leeward) side, creating a zone of low pressure. This, combined with the higher pressure on the concave (windward) side, creates lift that pulls the boat forward and sideways. The keel or centerboard counteracts the sideways motion, allowing the boat to move primarily forward. I've found that understanding this principle is key to fine-tuning sail trim.

When you're sailing downwind, the principle changes. With the wind coming from directly astern, the sail acts less like a wing and more like a parachute. The sails are trimmed to capture as much of the wind as possible, with the primary force being drag that pushes the boat forward.

What are the various Parts of a Sail called?

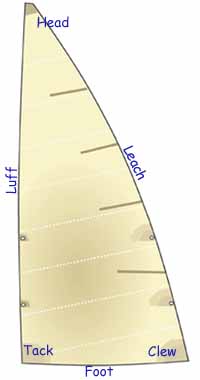

A sail, typically a modified triangle, has distinct parts that are essential to its function:

Naming the parts

Naming the parts- The Head: The top corner where the sail is hoisted via the halyard.

- The Tack: The forward-most corner, attached to the boat. On a mainsail, it connects to the gooseneck; on a headsail, it connects to the furling drum or deck.

- The Clew: The aft-most corner, where the sheet is attached to control the sail's angle.

- The Luff: The leading edge of the sail, from the head to the tack.

- The Foot: The bottom edge of the sail, from the tack to the clew.

- The Leach: The trailing edge, from the head to the clew. It's the most critical part of the sail for maintaining its shape and performance.

How to Trim & Tune Your Sails for Maximum Performance

Sail trim is a critical skill that directly impacts a sailboat's speed and efficiency. A sail's shape and angle can be manipulated to match the wind's strength and direction, ensuring you're getting the most out of your rig. If you want to learn more, our full guide is here: Mainsail Trim & Control: How to Maximize Power & Speed.

Understanding Sail Controls

- The Main Sheet & Traveler: The main sheet controls the sail's angle to the wind, while the traveler adjusts the boom's position relative to the boat's centerline, allowing you to fine-tune the sail's shape and twist.

- The Outhaul: This line tightens or loosens the foot of the sail, controlling the depth of the sail's lower section. A tighter outhaul flattens the sail for stronger winds, while a looser setting creates a deeper, more powerful shape for light air.

- The Cunningham: This control adjusts the tension on the luff (leading edge) of the mainsail. Pulling it down moves the draft (the deepest part of the sail's curve) forward, which is effective in stronger winds.

- The Vang (or Kicker): The vang pulls the boom down toward the deck. It's crucial for controlling the mainsail's twist, especially when sailing on a reach or downwind, to prevent the boom from lifting and losing its shape.

Reading the Telltales

Telltales are small ribbons attached to your sails that show the airflow. Proper sail trim is achieved when the telltales on both the windward and leeward sides of the sail stream back horizontally. If the windward telltale is fluttering, the sail isn't trimmed closely enough. If the leeward telltale is stalling or lifting, the sail is sheeted in too far.

How is a Sail's Area Calculated?

Calculating a sail's area is crucial for determining a sailboat’s sail area-to-displacement ratio, a key metric for performance. Since most sails are triangular, the formula's straightforward:

Area = half the base times the height

However, because the edges of most sails are curved (a feature known as "roach" on the leech), sailmakers use more complex measurements and computer software to achieve a precise result. For a more detailed look, check out our guide: Understanding Sail Area: A Simple Guide to Calculating Sail Dimensions.

What are the Best Materials & Constructions for Sailboat Sails?

Sail materials and construction methods have evolved significantly from traditional woven cotton to high-tech synthetics and composites. The choice depends on a balance of performance, durability, and cost. For a complete guide, check out How to Choose Sailcloth: A Guide to the Best Materials for Your Boat.

Sail Materials: A Comparison

| Material | Pros | Cons | Ideal For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dacron (Woven Polyester) | Affordable, highly durable, excellent UV resistance, easy to repair. | Stretches over time, leading to loss of shape & performance. Heavier than high-tech materials. | Cruising & day sailing, where longevity & durability are paramount. |

| Laminate Sails | Superior shape-holding & lower stretch than Dacron. Lighter weight for a given strength. | More expensive, can delaminate over time, less durable, & more susceptible to damage from folding. | Performance cruising & club racing. |

| High-Performance Fibers | Extremely high strength-to-weight ratio, minimal stretch, excellent shape-holding. | Very expensive, some fibers are highly sensitive to UV light (Kevlar) or bending/flogging (Carbon). | Serious racing & Grand Prix yachts. |

Construction Methods:

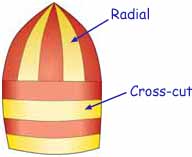

- Cross-Cut: The most traditional method, with panels laid out parallel to each other. It's best suited for woven Dacron, as it aligns the strong fill threads with the primary load from the leech. It's more affordable but stretches more over time.

- Radial Cut (Bi-radial & Tri-radial): Panels radiate from the corners of the sail, aligning the fabric with the primary load paths. This minimizes stretch and improves shape-holding. It's common for spinnakers and higher-end headsails.

- Molded (3Di): A modern, high-tech process where sails are built on a 3D mold using resin-impregnated filament tapes. This eliminates seams and creates a perfectly shaped, incredibly strong sail with virtually no stretch. This is a very expensive option for the highest-performance applications.

There’s a reason Dacron's been the go-to sailcloth for so long; it's durable and reliable. If you want to know more, read our article: Why Dacron Sails are Still the Best Choice for Cruising. On the flip side, many sailors wonder about the pros and cons of newer technologies. Our article, Are Laminate & 3Di Sails Worth It for Your Cruiser? addresses that very question.

What are the Main Types of Sailboat Sails & Their Uses?

An extensive sail wardrobe is part of being a well-equipped sailor. Here's a rundown of common sail types:

- Mainsail: The primary sail, located behind the mast. It provides the majority of the drive and along with the headsail, creates the slot effect for upwind performance.

- Jib: A headsail that doesn't overlap the mast. Jibs are versatile and perform well upwind in moderate to strong winds.

- Genoa: A larger headsail that overlaps the mast. Genoas provide extra power in light to moderate winds. Many cruising boats use a large roller-furling genoa that can be partially reefed to act as a smaller headsail.

- Spinnaker & Gennaker: Large, lightweight, balloon-shaped sails used for downwind sailing. Spinnakers are symmetrical & require a spinnaker pole, while gennakers (asymmetric spinnakers) are easier to handle as they don't require a pole. These are ideal for long-distance, downwind passages. Find out if they're right for you in our article: A Cruiser's Guide to Spinnakers & Gennakers.

- Storm Sails: Small, durable, and highly visible sails (often orange) designed for use in heavy weather. A storm jib and trysail (a small mainsail hoisted on a separate track) are essential safety gear for offshore passages. Find out more in Storm Sails: Essential Safety Gear for Offshore Sailors.

Sail Care & Maintenance

our sails are a significant investment. Proper care extends their life, maintains their performance, and can save you money on costly repairs. To get a comprehensive overview, take a look at our full guide: A Sailor's Guide to Sail Maintenance

Year-Round Maintenance

- Regular Inspection: Routinely check for chafe, small tears, loose stitching, and mildew. Catching these issues early can prevent a major failure.

- Washing & Drying: Wash sails with fresh water at the end of a season and be sure they're completely dry before long-term storage to prevent mildew and damage to the stitching. Never use bleach on nylon or Dacron.

- UV Protection: The sun is the number one enemy of sailcloth. On a furling headsail, make sure the UV protection strip is in good condition. For mainsails, a cover's crucial when the boat isn't in use.

Professional Care

For off-season storage, many sailors choose to have their sails professionally inspected, cleaned, and repaired by a sailmaker. They can spot minor issues that you might miss and ensure your sails are in top condition for the next season.

Sail Safety & Handling

Understanding how to manage your sails in all conditions is fundamental to safe sailing. My own experiences have shown me that being prepared is always the best policy. For a complete guide to safe sailing, read Sail Safety: A Guide for Safe & Enjoyable Sailing.

Reef Early, Reef Often

The golden rule of sailing is to reef early. As the wind increases, reduce the sail area before you feel overpowered. This keeps the boat balanced, reduces heeling, and makes the boat easier to handle. It's much easier to put a reef in when the conditions are still manageable than to wait for a full gale.

Heavy Weather Sail Handling

In strong winds and large seas, knowing your sail options is a must. A deeply reefed mainsail and a smaller, roller-reefed headsail can keep the boat moving comfortably. When the wind gets truly dangerous, switching to your storm jib and storm trysail will provide just enough power to maintain steerage while significantly reducing the strain on your boat and crew.

Sail Repair & Knowing When to Replace Your Sails

Your sails are subjected to constant stress, UV radiation, and chafe, making regular inspection and maintenance essential.

Onboard Sail Repair

Every sailor should carry a basic sail repair kit with sail repair tape, a strong needle, and waxed thread. For minor tears and chafe, sail repair tape is an effective temporary fix. A more durable hand-stitched patch can be applied later, but for major damage, the sail should be taken to a professional sailmaker. It's often the small fixes that prevent a major failure at sea.

Assessing Sail Lifespan

A sail's lifespan is typically measured in hours of use, but a visual and tactile inspection is the best indicator.

- UV Damage: Look for areas where the cloth is discolored or brittle. A sail that feels "crunchy" still has life, but a sail that feels soft and limp has lost its integrity and should be considered for replacement.

- Fabric Wear & Tear: Inspect high-stress areas like the leech, head, and corners for signs of delamination (on laminate sails), tears, and chafe.

- Loss of Shape: The most significant sign that a sail needs replacement is when it loses its designed shape. A sail that becomes "baggy" and refuses to hold a proper airfoil shape won't perform efficiently anymore.

What are the Pros & Cons of Roller Furling Sails?

Roller furling systems, both for headsails and mainsails, have become a staple for cruising sailors because of their convenience. As an experienced sailor, I've had both positive and negative experiences with them.

Headsails:

- Pros: Ease of use, sail can be quickly deployed or reefed from the cockpit, eliminates the need to change headsails on a pitching foredeck.

- Cons: Can create a less-than-ideal sail shape when reefed, which reduces efficiency. A hanked-on storm jib is often a more reliable option in true heavy weather.

Mainsails:

- Pros: Ultimate convenience for reefing and stowing.

- Cons: More complex and prone to jamming than slab reefing. The furled sail can create a less efficient sail shape. I've always preferred the simplicity and reliability of a slab reefing system with lazy jacks, but I know plenty of offshore sailors who'd disagree with me. The choice often comes down to personal preference and sailing style.

My personal preference? Easy, for me it's simplicity and reliability every time:

- A furling jib,

- A hanked-on staysail (if used) and

- Slab reefing on the mainsail.

This article was written by Dick McClary, RYA Yachtmaster and author of the RYA publications 'Offshore Sailing' and 'Fishing Afloat', member of The Yachting Journalists Association (YJA), and erstwhile member of the Ocean Cruising Club (OCC).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What's the best sail material for offshore cruising?

What's the best sail material for offshore cruising?

Dacron is widely considered the best choice for offshore cruising. Its durability, longevity, and affordability outweigh the performance trade-offs for most long-distance sailors.

What is sail shape and why's it important?

What is sail shape and why's it important?

Sail shape, or "draft," is the curvature of the sail. A sail's shape is crucial for performance. You can adjust it with sail trim controls like the cunningham, outhaul, and vang.

Do I need a spinnaker?

Do I need a spinnaker?

A spinnaker or gennaker isn't essential for coastal cruising, but it can make long, downwind passages significantly more enjoyable by providing power in light winds and eliminating the need to motor.

What's the difference between a jib & a genoa?

What's the difference between a jib & a genoa?

A jib is a headsail that doesn't extend past the mast. A genoa, on the other hand, is a larger headsail that overlaps the mast and mainsail. Genoas are used to provide more power, especially in light winds, while jibs are more manageable in stronger winds.

Is in-mast furling a good option for a cruising mainsail?

Is in-mast furling a good option for a cruising mainsail?

In-mast furling offers incredible convenience for stowing your mainsail without leaving the cockpit. However, it's a complex system that can be prone to jamming if not maintained properly. Sailors who value simplicity and reliability often prefer a traditional slab reefing system.

How should I store my sails during the off-season?

How should I store my sails during the off-season?

It's best to have your sails professionally inspected & cleaned by a sailmaker before storing them. If you're doing it yourself, make sure they're completely dry to prevent mold and mildew. Fold them loosely in a breathable sail bag and store them in a cool, dry place, away from rodents.

Sources Used

- Yachting.com - "Sailing Tech 2025: the yachting of the future" https://www.yachting.com/en-gb/news/sailing-tech-the-future-of-sailing

- GetBoat.com - "Innovations in Sail Measurement Technology - Yacht News & Trends" https://www.getboat.com/blog/innovations-in-sail-measurement-technology

- Reddit r/sailing - "What are some sailboat innovations as of recent years that excite you?" https://www.reddit.com/r/sailing/comments/1fudi3z/sailing_technologies/

- https://www.google.com/search?q=MySailing.com.au - "Next-Gen Data-Driven Sail Performance is Here" https://www.mysailing.com.au/next-gen-data-driven-sail-performance-is-here/

- Wikipedia - "Sail" https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sail

- SAILSetc - "SAILMAKING NOTES" https://www.sailsetc2.com/downloads/TI%2020%20Sailmaking%20notes.pdf

- SailTrader - "Sail Material Guide - Mainsails & Headsails" https://sailtrader.com/sail-material-guide-mainsails-and-headsails/

- Quantum Sails - "Demystifying Modern Cruising Sail Design" https://www.quantumsails.com/en/resources-and-expertise/articles/building-a-better-cruising-sail

- Wave Train - "MODERN CRUISING SAILS: Sail Construction & Materials" https://wavetrain.net/2021/04/06/modern-cruising-sails-sail-construction-materials/

- Mallorca Sailing - "Types of Sails & How They are Used" https://www.mallorcasailingacademy.com/articles/types-of-sails-and-how-they-are-used

- PierShare Blog - "Sailing Stats: Types of Sails & What they Do" https://blog.piershare.com/blog/sailing-stats-types-of-sails-and-what-they-do

- Discover Boating - "A Comprehensive Guide to 8 Types of Sails" https://www.discoverboating.com/resources/types-of-sails

- GJW Direct - "A complete guide to types of sails" https://www.gjwdirect.com/blog/a-complete-guide-to-types-of-sails/

- Saltwater Journal - "Beginner's Guide to Types of Sails" https://www.saltwaterjournal.life/blog/types-of-sails

- YACHT - "Sail material: The difference between fabric, laminate & membrane" https://www.yacht.de/en/sail/sail-materials-the-differences-between-fabric-laminate-and-membrane/

- Quora - "What are the pros & cons of different sail materials used in modern sailing?" https://www.quora.com/What-are-the-pros-and-cons-of-different-sail-materials-used-in-modern-sailing

- Wrist Envy - "Top Quality Sailcloth Materials | Your Ultimate Guide" https://www.wristenvy.com/top-quality-sailcloth-materials/

- North Sails - "FIBERS & FABRICS: A SAILOR'S GUIDE | SAILCLOTH FABRIC GUIDE" https://www.northsails.com/sailing/articles/fibers-and-fabrics-a-sailors-guide

Recent Articles

-

Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 45.2 Review: Specs, Ratios & Cruising Analysis

Jan 13, 26 05:48 PM

Discover the Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 45.2. A comprehensive guide to its Philippe Briand design, performance ratios, Kevlar hull construction, and offshore cruising capability. -

Beneteau Oceanis 400: Expert Review, Specs & Performance Analysis

Jan 12, 26 07:40 AM

A comprehensive guide to the Beneteau Oceanis 400 sailboat. We analyse the Jean-Marie Finot design, performance ratios, interior layouts, and offshore cruising capabilities for prospective buyers. -

Hunter Passage 42 Sailboat: Specs, Performance & Cruising Analysis

Jan 11, 26 05:31 AM

Explore the Hunter Passage 42 sailboat. Includes detailed design ratios, performance analysis, interior layout review, and expert cruising advice for owners.