- Home

- Reefing

Reefing a Sail: The Ultimate Guide to Control & Safety at Sea

In a Nutshell...

Reefing a sail is simply about taking control of your boat. It means reducing your sail area to match the wind's strength. It's the most fundamental skill for keeping your boat safe, your crew happy, and your passage comfortable. When you reef early, you prevent your boat from fighting the wind, allowing it to move through the water with grace and power, just as it was designed to. This guide covers the 'what, why, and how' of reefing, from reading the tell-tale signs to mastering the various systems you'll find on a cruising yacht.

Headsail reefing gear. This one is the Profurl furling system.

Headsail reefing gear. This one is the Profurl furling system.Table of Contents

What is Reefing a Sail & Why is it Crucial for Every Sailor?

Reefing a sail is all about striking the right balance. You're not surrendering to the wind; you're just trimming your canvas to harness its power safely. As any seasoned sailor will tell you, a boat that's overpowered isn't a fast boat—it's a tired boat.

- Safety First: An overpowered boat is a recipe for disaster. That gut-wrenching feeling of excessive heeling puts an incredible, unnecessary strain on your mast, rigging, and sails. Left unchecked, it can lead to a broach—a truly terrifying loss of control. Reefing is your best defence, keeping the boat stable and the motion predictable.

- A Happy Crew Makes a Happy Boat: No one enjoys being constantly thrown around. A boat that's overpowered is a violent, uncomfortable place to be. It wears out the crew, makes cooking and navigating a nightmare, and can quickly turn a fun trip into a miserable slog. Reefing early smooths out the ride and makes the passage a pleasure for everyone on board.

- The Myth of Speed: You'd think more sail means more speed, right? Not so. An overpowered sail distorts its shape, turning it into a giant brake. I've often seen un-reefed boats struggling and wallowing in a blow, while a well-reefed yacht sails right past them, slicing smoothly through the waves. A properly reefed sail maintains its efficient aerodynamic shape, giving you better speed and control.

- Look After Your Gear: I've been sailing for decades, and I've seen firsthand what happens when you push gear too hard. The immense forces of an overpowered sail will stretch your sails out of shape and put undue stress on every block, line, and fitting. Reefing is simple preventative medicine that will significantly extend the life of your expensive equipment. For more in-depth advice, our guide on A Sailor's Guide to Sail Maintenance is an excellent resource.

Forget the idea that easing the sheets is enough. That's a temporary fix for a gust. Reefing is a permanent, strategic solution for sustained winds. My advice has always been the same: "When in doubt, reef." It's a golden rule for a reason, and it’s always better to put a reef in an hour too early than a minute too late.

When to Reef: Reading the Signs & Anticipating Conditions

Learning to feel your boat is a skill that comes with time, but there are some clear signals that it's time to shorten sail. While a wind gauge is a useful tool, the real clues come from the boat herself.What are the Key Indicators that it's Time to Reef?How Can I Anticipate the Need to Reef?

- Excessive Heeling: Is your boat consistently heeled over more than you'd like? A lean of over 20-25 degrees isn't just uncomfortable; it's slowing you down and pushing your rudder to its limit.

- That Heavy Helm: Do you feel a strong, relentless pull on the wheel or tiller? That "weather helm" is a clear sign that your rudder is fighting a losing battle to keep you on course. It's a tiring feeling and a sure sign you're overpowered.

- The Water's Not Giving You More Speed: You've got more wind, but the boat's speed isn't climbing with it. You've hit your hull speed, and any extra wind is just putting a heavy strain on your rig for no reward.

- The Sound of Your Sails: Listen to your sails. If you hear them flapping or "flogging" violently at the luff or leech, they're simply being overpowered and distorted. It's the sound of inefficiency and strain.

- Your Crew are Uncomfortable: Honestly, this is often the best indicator. If your crew are bracing against the motion, getting seasick, or looking tired, it's time to make things easier on them. A happy crew is a safe crew.

The best sailors are always thinking ahead. You should be proactive, not just reacting to what the weather is doing.

- Check the Forecast: Before a passage, especially an overnight one, always review the forecast. If strong winds or squalls are predicted, take a proactive approach and put a reef in before you even leave the harbour. It’s far easier to do it calmly in daylight than frantically in a sudden downpour.

- Look at the Sea State: Rough, confused seas add a huge amount of strain. You may need to reef much earlier in these conditions than the wind speed alone would suggest, just to make the ride safer and more comfortable.

- Consider Your Sailing Angle: Sailing close-hauled—upwind—is the most powerful point of sail and usually requires reefing first. But don't forget that on a downwind run, you may need to reduce sail to maintain control and prevent an accidental broach. For more on this, our guide on Understanding Wind & Sail Trim: A Guide to Optimal Performance will get you up to speed.

What are the Main Types of Reefing Systems?

The system you use to reef a sail depends on your boat’s rigging and sail plan. Here’s a breakdown of the most common methods, with further information on How to Choose the Right Reefing System for Your Boat.

| System | Description | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

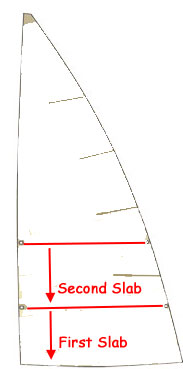

| Slab (Jiffy) Reefing | Utilises reinforced eyelets (cringles) on the sail that are pulled down to the boom to create a new, smaller sail. | Very efficient, effective, maintains good sail shape. | May require crew to go on deck near the mast; can be more physically demanding. |

| Single-Line Reefing | A variation of slab reefing where a single line controls both the luff and leech reefing points from the cockpit. | Convenient, simple, minimal time on deck. | Can be less efficient for deeper reefs due to line friction & geometry. |

| Two-Line Reefing | A variation of slab reefing using separate luff and leech lines, both typically led back to the cockpit. | Offers excellent control, robust for deeper reefs, allows for precise tensioning. | Requires more lines and hardware. |

| In-Mast Furling | The mainsail rolls into a hollow mast. | Infinitely variable sail area, operated from cockpit, very convenient. | Compromised sail shape, less sail area than slab reefing, potential for jamming. | In-Boom Furling | The mainsail rolls into a rotating boom. | Combines convenience of furling with better sail shape & more area retention. | More complex and expensive than other systems. |

For a deeper understanding of specific systems, explore our detailed guides on slab reefing: The Basics of Jiffy Reefing: A Sailor's Guide and Single-Line Reefing: Is It the Best System for You?

For headsails, headsail roller furling is the standard. This system allows the jib or genoa to be rolled around the forestay from the cockpit, offering quick and easy sail area adjustment. While convenient, a partially furled headsail may have a less-than-ideal shape, which is why features like a foam luff or a double swivel are crucial for maintaining performance. For a complete guide to headsail furling, see our article on Mastering Your Roller Furling Headsail: A Guide to Jibs & Genoas.

When it comes to mainsail furling, systems like in-mast and in-boom furling have become popular for their ease of use. For more information, read our in-depth article on Mainsail Furling: In-Mast & In-Boom Systems Explained.

How to Reef the Mainsail

While every boat has her own quirks, the basic principles for slab reefing are always the same. For a comprehensive walkthrough, see our detailed instructions on Mainsail Reefing: A Step-by-Step Guide.

Reefing the main a slab at a time

Reefing the main a slab at a time- Prepare: First, make sure your reefing lines are clear and ready to run. If you've got a lazy jack system, set it so it's ready to catch the sail as you lower it. For more on this, read Lazy Jacks: How They Simplify Mainsail Handling.

- Adjust Course: Head up slightly into the wind. This takes the pressure off the sail and makes the job so much easier.

- Ease Controls: Release your mainsheet and ease the vang to take the load off the boom. If you have a topping lift, now's the time to set it to support the boom's weight.

- Lower Halyard: Slowly and deliberately lower the main halyard. Ease the sail down just enough so the first reefing cringle lines up with your gooseneck hook.

- Secure the Luff: Now, hook that luff cringle onto the ram’s horn or dedicated hook at the gooseneck. This is your new tack, and it needs to be secure as it'll take the primary load.

- Secure the Leech: Pull the reef clew line (outhaul) tight. This pulls the leech cringle down and back, establishing the new foot of the sail.

- Re-Tension Halyard: Once both points are secure, re-tension the main halyard firmly. Proper luff tension is absolutely vital for a good sail shape and performance.

- Tidy Up: Use reefing ties or shock cord to gather up the excess sail material on top of the boom. Just make sure you tie them under the foot of the sail and around the boom, never through the sail's eyelets. This prevents chafing and tearing.

- Re-Trim: With the reef in, adjust your mainsheet and vang. You'll likely need to sheet in more tightly to get the perfect sail shape.

Here, the first reef has been taken in. The flying cringle is in place in the captive hook. Note the blue mark on the halyard which indicates where the sail should be lowered to.

Here, the first reef has been taken in. The flying cringle is in place in the captive hook. Note the blue mark on the halyard which indicates where the sail should be lowered to.Advanced Reefing Tactics & Preparation

For a confident sailor, reefing is a strategic part of passage planning. For an in-depth look at managing challenging conditions, read our guide on Advanced Reefing Tactics for Heavy Weather Sailing.

- Deep Reefing & Storm Sails: I've been in truly nasty conditions where even the deepest reef wasn't enough. Beyond that point, dedicated storm sails—a trysail (in place of the main) and a storm jib—are your lifesavers. They're built for ferocious winds and give you just enough power to maintain control. For any serious offshore sailor, a proper storm sail inventory isn't a luxury; it's a key safety measure.

- Reefing at Different Points of Sail: The standard procedure is to head up into the wind to reef, but in heavy seas or when sailing downwind, that's not always the safest option. Sometimes, you can use your jib to blanket the mainsail, taking the pressure off while you work. It's a great tactic that reduces the violent motion and makes the whole process safer. On a downwind course, you might even furl your headsail first to slow down and maintain better control.

- Practice & Maintenance: The best way to build confidence is to practice. Don't wait for a storm; run reefing drills in moderate conditions until it feels like second nature. Also, make sure your lines and blocks are always running freely. A simple but effective trick is to mark your halyard with a permanent marker at each reef point. No more guesswork!

- The Best Order: As a general rule, on a mainsail-driven boat, reef the mainsail first. It has the biggest impact on stability. On a headsail-driven boat, or when you're sailing downwind, it's often more effective to reef the headsail first to maintain control and reduce the risk of broaching. The right call comes down to your vessel and the conditions.

Heaving-To: An Essential Storm Tactic

When conditions deteriorate beyond the point where even a deep reef is manageable, heaving-to is a vital heavy-weather skill. It's a way of putting the boat on pause, allowing it to safely ride out the storm. It involves balancing the jib and rudder to stop the boat's forward motion, which reduces strain on the boat and gives the crew a chance to rest and reassess the situation. To learn how to do it correctly, read our full guide on Heaving-To: An Essential Storm Tactic for Sailboats.

Summing Up

Reefing a sail isn't a struggle; it's a fundamental skill that transforms your relationship with the wind. By understanding when and how to do it, you can make your boat faster, your crew more comfortable, and your sailing safer. Embrace the "reef early" philosophy and make a regular habit of practising. It's the mark of a truly capable sailor.

While reefing focuses on safely reducing your working sail area, there are other systems designed for managing specialised sails. To learn about top-down furlers and how they help handle light-wind sails like asymmetric spinnakers and Code Zeros, check out our guide on Handling Asymmetric Spinnakers & Code Zeros: A Guide to Top-Down Furling.

This article was written by Dick McClary, RYA Yachtmaster and author of the RYA publications 'Offshore Sailing' and 'Fishing Afloat', member of The Yachting Journalists Association (YJA), and erstwhile member of the Ocean Cruising Club (OCC).

FAQs: Your Quick Answers to Common Questions

How much wind is too much for full sail?

How much wind is too much for full sail?

There's no magic number. It really depends on your boat's design and rig. For most cruising boats, you'll probably want to have the first reef in once the wind gets up to about 15-20 knots.

Is it safe to reef a sail alone?

Is it safe to reef a sail alone?

Yes, it is, but it takes practice and a well-planned system. The key is to have all your lines led back to the cockpit. This keeps you safe and on-station without needing to venture onto a heaving deck.

What is the difference between reefing and furling?

What is the difference between reefing and furling?

Reefing is the process of reducing a sail's size using a system like slab reefing, while furling is the act of rolling a sail around a stay or into a mast/boom. Both are methods of reducing sail area, just different approaches.

Should I reef my headsail or mainsail first?

Should I reef my headsail or mainsail first?

Typically, you'd reef the mainsail first since it has the biggest impact on stability and heeling. But when sailing downwind or on a boat that relies more on its headsail, it can be more effective to furl the jib first.

Do I need a lazy jack system to reef?

Do I need a lazy jack system to reef?

No, you don't need one, but I wouldn't go without one on a cruising boat. They make the whole process so much easier by cradling the sail as it's lowered, preventing it from spilling all over the deck.

Recent Articles

-

Planning Your Sailboat Liveaboard Lifestyle: An Ocean Sailor's Guide

Dec 06, 25 05:18 AM

Seasoned sailors share their methodical risk analysis for planning a secure Sailboat Liveaboard Lifestyle, covering financial, property, and relationship risks. -

Marine Cabin Heaters: The Expert’s Guide to Comfort & Safety at Sea

Dec 05, 25 06:52 AM

Choose the best Marine Cabin Heaters for your vessel. Expert advice on diesel, paraffin, and hot water systems for year-round cruising comfort. -

Marine Water Heating Systems: Free Hot Water from Your Boat's Engine

Dec 03, 25 05:06 PM

Tap into your engine's heat to get free hot water on board. An experienced ocean sailor's guide to marine water heating systems, calorifiers & safety.