Mainsail Furling: In-Mast & In-Boom Systems Explained

In a Nutshell...

Roller furling mainsail systems, including both in-mast and in-boom furling, offer a significant upgrade in safety, convenience, and sail preservation for cruising sailors. While older systems had performance and reliability issues, modern designs have largely overcome these drawbacks with advancements in materials and sail technology. These systems allow for infinite reefing points from the safety of the cockpit, protect the sail from harmful UV rays, and greatly simplify sailing for single-handed or short-handed crews. The choice between an in-mast and in-boom system often comes down to a preference for ultimate ease of use versus better sailing performance.

An in-mast furling mainsail can never be completely furled within the mast owing to the stiffness of the reinforcing in the clew of the sail

An in-mast furling mainsail can never be completely furled within the mast owing to the stiffness of the reinforcing in the clew of the sailTable of Contents

- The Roller Furling Mainsail: What You Need to Know

- In-Mast vs. In-Boom Furling: Getting to Grips With the Differences

- Modern Sails Have Come a Long Way

- What Are the Key Operational & Maintenance Procedures?

- What Are the Emergency Procedures for a Furling System Jam?

- What Is the Cost/Benefit of Furling Systems?

- Prominent Manufacturers of Mainsail Furling Gear

- Summing Up

- FAQs

The Roller Furling Mainsail: What You Need to Know

Not so many years ago, I would have told you that roller furling mainsail systems, whether in-boom or in-mast, were so performance-limiting and prone to jamming that I wouldn't be wanting either on my boat any time soon.

But my goodness, how things have changed. Since those days, modern in-mast and in-boom systems have seen significant advancements in design, materials, and reliability. The stated drawbacks are now far less relevant or have been completely overcome.

Beyond the obvious benefit of making reefing a quick and easy operation, these systems offer a host of other advantages that are a game-changer for anyone who spends a lot of time on the water.

- Convenience & Safety: Furling from the cockpit entirely eliminates the need to go on deck to reef or stow the mainsail. This is particularly crucial in foul weather or at night, significantly enhancing crew safety. I can still vividly recall the stress of wrestling with a flogging mainsail in a gale; these systems make that a distant, thankfully largely forgotten memory.

- Infinite Reefing Points: Unlike the fixed reef points of slab reefing, roller furling allows for precise and continuous adjustment of sail area. You can perfectly match the sail to the prevailing wind conditions, maximising both comfort and performance.

- Sail Preservation: When furled, the mainsail is neatly stowed within the mast or boom, protecting it from harmful UV rays, chafe, and environmental degradation, thereby extending its lifespan.

- Ease of Single-Handing/Short-Handing: For those sailing with limited crew, these systems drastically reduce the physical effort and coordination required to manage the mainsail, making larger boats far more accessible.

In-Mast vs. In-Boom Furling: Getting to Grips With the Differences

The choice between an in-mast and in-boom furling system is one of the most significant decisions a sailor can make when specifying a new yacht or undertaking a major refit. While both systems share the core benefit of cockpit-based sail handling, their design and impact on a yacht's performance differ considerably.

I've put together a table to lay out the key features, pros, and cons of each, which should help you when weighing up the options.

| Feature / System | In-Mast Furling | In-Boom Furling |

|---|---|---|

| Pros | Maximum safety (fully contained in mast); Minimal deck clutter; Excellent UV protection. | Better sail shape (full battens, more roach); Lower centre of gravity when reefed/stowed; Easier access to sail for repairs/maintenance if jammed. |

| Cons | Sail shape limitations (historically, less roach); Higher centre of gravity (sail weight aloft); Can be more challenging to clear a jam aloft. | Requires precise boom angle for furling; Boom can be larger/heavier; Sail exposed to elements in boom slot (less UV protection). |

| Sailing Performance | Generally flatter sail, less powerful upwind (though modern sails improve this). | Better upwind performance with full battens; minimal impact on stability. |

| Installation | Often requires new mast; complex internal mechanisms. | Requires new boom; careful alignment with mast. |

| Maintenance | Lubrication of internal drive, inspection of slot. | Lubrication of furling drum, cleaning boom slot. |

| Suitability | Cruisers prioritising ultimate ease and safety. | Performance-minded cruisers, those wanting better sail shape. |

Modern Sails Have Come a Long Way

Historically, roller furling mainsails were limited to a flat cut with minimal roach (the curved part of the sail's trailing edge) to ensure smooth furling. This resulted in a less powerful sail, especially when sailing upwind.

Thankfully, those days are long gone. Modern sailmakers have overcome this limitation with advancements in sail design. In-boom systems can use full-length battens to maintain optimal shape and a full roach, giving them excellent upwind performance.

In-mast furling sails, on the other hand, are designed with vertical battens along the leech. While these aren't full length, they help to flatten the sail and control its shape as it furls, preventing it from getting baggy. Advanced materials, such as laminates or 3Di technologies, also help to distribute loads more efficiently, preventing the excessive stretching common with older designs. The upshot? A well-designed modern furling mainsail can deliver performance that gives a traditional slab-reefed sail a real run for its money.

What Are the Key Operational & Maintenance Procedures?

Correct operation and regular maintenance are crucial for the reliable functioning of any furling system and preventing common issues.

Operational Procedures

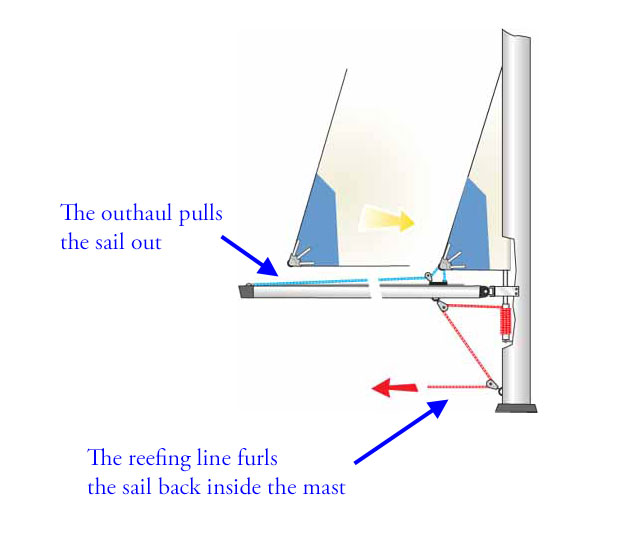

- In-Mast Furling: To unfurl, head slightly off the wind, release the furling line, and steadily pull on the outhaul. To furl, head into the wind (or slightly off depending on the specific furler and wind direction), ensure the boom is at the correct angle (often aided by a rod kicker), maintain a slight tension on the outhaul, and steadily pull on the furling line. The key is to create a tight, even roll to prevent creases and jams.

- In-Boom Furling: The boom angle relative to the mast is critical, typically around 87 degrees. Before hoisting, use the topping lift and vang to set this angle. When hoisting or furling, ease the mainsheet and winch in or out on the furling line while managing the halyard.

For both systems, consistent tension on all lines prevents overrides and messy furling. Never use a winch to force the system; you'll only end up causing significant damage.

Maintenance Best Practices

- Regular Rinsing: Freshwater rinsing of the furling drum and internal mechanisms is essential to remove salt and dirt.

- Lubrication: Lubricate moving parts, such as bearings and swivels, with a suitable dry lubricant. Avoid heavy grease, which attracts grime.

- Line Inspection: Regularly inspect the furling line itself and replace it at the first sign of wear.

- Preventative Checks: For in-boom systems, ensure the boom slot is free of debris. For in-mast systems, check for any obstructions at the mast slot.

A common troubleshooting tip for a minor jam is to relieve all tension, then reapply it while trying to furl or unfurl the sail. Often, a small adjustment in boat angle or line tension can clear the issue.

What Are the Emergency Procedures for a Furling System Jam?

Despite their reliability, mechanical systems can fail, and a jammed furling mainsail can be a serious issue, particularly in a sudden squall or gust. Knowing the correct emergency procedures is paramount for crew safety and preventing damage.

1. Initial Response: Don't Force It ⚠️ If the system jams, the first and most crucial rule is to never force it with a winch. Forcing the sail can lead to catastrophic damage to the mast, boom, or the furling mechanism itself. Instead, immediately release all tension on the lines (furling line, outhaul, mainsheet) and try to sail the boat to a different point of sail to relieve pressure on the sail. Often, a small change in heading—for example, a bear away or a luff up—can be enough to clear a minor bind.

2. Manual Unfurling & Dowsing If the jam cannot be cleared from the cockpit, you must prepare to deal with the situation manually. The ultimate emergency procedure is to disconnect the sail from the furling foil and hoist it down. This is an extremely challenging task at sea.

- Secure a Spare Halyard: If possible, attach a spare halyard to the head of the sail before you begin to un-cleat the main halyard.

- Release the Tack: Disconnect the sail's tack (the corner at the gooseneck) from the furling drum or boom foil.

- Lower the Sail: Carefully ease the main halyard to lower the sail, while someone on deck works to pull the sail free from the mast or boom slot. This can be a messy and chaotic process, as the sail will not be neatly furled.

- Secure on Deck: Once the sail is down, it must be secured on deck to prevent it from blowing away. This is where your preparedness with spare sail ties or bungees will be invaluable.

3. Emergency Repairs For an in-mast system, a halyard wrap can often be cleared by a crew member going aloft to untangle it, but this should only be attempted in calm conditions and with proper safety equipment. For other jams, such as a damaged bearing or a broken line, there may be little that can be done at sea beyond dowsing the sail. Having a small emergency repair kit, including durable tape and spare shackles, can sometimes provide a temporary fix.

The best emergency procedure is always a preventative one. Regular maintenance and a thorough inspection of your furling system before any long passage will drastically reduce the likelihood of a critical failure.

What Is the Cost/Benefit of Furling Systems?

The initial cost of installing a new roller furling mainsail system is significant. For a 40-foot yacht, a new in-mast furling system could cost anywhere from £10,000 to over £20,000, depending on whether it is a manual or electric system and the materials used (e.g., carbon fibre). In-boom systems can be priced in a similar ballpark, often requiring a new boom and a specifically cut, fully battened sail.

While the initial outlay is substantial, the value proposition extends well beyond the purchase price. The enhanced safety, reduced physical effort, and extended lifespan of the sail due to protected storage are all compelling benefits. For many cruisers, the increased enjoyment and peace of mind these systems provide more than justify the cost.

Furthermore, a well-maintained, modern furling mainsail system is generally viewed as a highly desirable feature for cruising yachts and can significantly enhance marketability. The fact that many modern production cruising boats offer these systems as standard or popular options reflects their growing acceptance and demand within the market.

Getting to grips with mainsail furling is just one part of a comprehensive approach to managing your sails and ensuring safety at sea. For a more detailed exploration of all sail types and handling methods, refer to our definitive guide, Reefing a Sail: The Ultimate Guide to Control & Safety at Sea.

Prominent Manufacturers of Mainsail Furling Gear

The primary types of furling systems are in-mast and in-boom. Within these categories, you can find manual, hydraulic, and electric versions. Electric and hydraulic systems are particularly popular on larger yachts, as they provide even greater ease of use.

Prominent manufacturers in this space include:

- Seldén Mast: A major supplier of both in-mast and in-boom solutions, commonly found on production boats.

- Leisure Furl (Forespar): A well-established brand for in-boom systems, known for reliability and often featuring an integral sail cover.

- Hall Spars: Offers high-performance carbon in-boom systems, typically for larger yachts.

- Schaefer Marine: Develops innovative boom furlers designed to address common issues.

- Facnor & Profurl: Offer a wide range of furling systems, including those that can be retrofitted with electric drives.

Summing Up

While the thought of a roller furling mainsail may have once been met with scepticism, modern advancements have made these systems a highly reliable and desirable option for cruisers. They represent a significant shift from traditional sail handling, prioritising safety, convenience, and ease of use. For the cruising sailor who values effortless sail management and the peace of mind that comes with staying out of harm's way, a modern furling system is an invaluable investment. It's not just about convenience; it's about making sailing more accessible and safer for everyone on board.

This article was written by Dick McClary, RYA Yachtmaster and author of the RYA publications 'Offshore Sailing' and 'Fishing Afloat', member of The Yachting Journalists Association (YJA), and erstwhile member of the Ocean Cruising Club (OCC).

FAQs

Are roller furling mainsails difficult to install?

Are roller furling mainsails difficult to install?

Installation, particularly for in-mast systems, is complex and often requires a new mast. It's a job best left to professional riggers to ensure correct alignment and functionality.

What should I do if my furling system jams?

What should I do if my furling system jams?

First, stop trying to force it. Relieve tension on all lines, then re-tension and try again, perhaps with a slight adjustment to the boat's heading. If a jam persists, it may be due to a halyard wrap or an issue with the sail's roll, and you may need to physically inspect the mast.

Do in-mast furling systems really affect a boat's performance?

Do in-mast furling systems really affect a boat's performance?

While older systems did limit sail shape, modern in-mast sails with vertical battens offer significantly improved performance, reducing the performance penalty to a minimum.

Can I use a regular mainsail with a furling system?

Can I use a regular mainsail with a furling system?

No, a regular mainsail cannot be used. Furling mainsails must be specifically designed and cut for the system, often with a different luff attachment and sometimes vertical battens to manage sail shape.

How do I maintain a roller furling mainsail?

How do I maintain a roller furling mainsail?

Regular maintenance involves freshwater rinsing to remove salt, lubricating moving parts, and inspecting lines for wear. Proper operation—especially maintaining tight, even tension—is the best preventative maintenance.

If you're looking for more in-depth answers to more complex questions on this topic, take a look at Mainsail Reefing & Furling: Your Questions Answered...

Sources Used

- Seldén Mast: https://www.seldenmast.com/

- Leisure Furl (Forespar): https://www.forespar.com/leisurefurl/

- Hall Spars: https://www.hallspars.com/

- Schaefer Marine: https://www.schaefermarine.com/

- Facnor: https://www.facnor.com/en/

- Profurl: https://www.profurl.com/en/

- Sailnet: https://www.sailnet.com/

- Yachting Monthly: https://www.yachtingmonthly.com/

Recent Articles

-

Planning Your Sailboat Liveaboard Lifestyle: An Ocean Sailor's Guide

Dec 06, 25 05:18 AM

Seasoned sailors share their methodical risk analysis for planning a secure Sailboat Liveaboard Lifestyle, covering financial, property, and relationship risks. -

Marine Cabin Heaters: The Expert’s Guide to Comfort & Safety at Sea

Dec 05, 25 06:52 AM

Choose the best Marine Cabin Heaters for your vessel. Expert advice on diesel, paraffin, and hot water systems for year-round cruising comfort. -

Marine Water Heating Systems: Free Hot Water from Your Boat's Engine

Dec 03, 25 05:06 PM

Tap into your engine's heat to get free hot water on board. An experienced ocean sailor's guide to marine water heating systems, calorifiers & safety.