- Home

- Cruising Yachts 40' to 45'

- Passport 40

The Passport 40 Sailboat

Specs & Key Performance Indicators

The Passport 40 sailboat was designed by Robert Perry and manufactured by Passport Yachts in Taiwan throughout the years 1978 to 1984

Published Specification for the Passport 40

Keel & Rudder Configuration: Full foil keel with a skeg-hung rudder.

Hull Material: Fiberglass (FRP).

Length Overall: 12.19m (40'0")*.

Waterline Length: 9.91m (32'6")*.

Beam: 3.66m (12'0")*.

Draft: 1.83m (6'0")*.

Rig Type: Cutter.

Displacement: 9,525 kg (21,000 lbs)*.

Ballast: 4,536 kg (10,000 lbs*).

Sail Area (main plus 100% foretriangle): 79.9m2 (860ft2)*.

Water Tank Capacity: 378.5 litres (100 US gallons).

Fuel Tank Capacity: 189.3 litres (50 US gallons).

Hull Speed: Approximately 7.7 knots.

Designer: Robert Perry.

Builder: Passport Yachts (various yards in Taiwan, including South Coast Marine and Ho Hsing Fiberglass Boat Co. Ltd.).

Year First Built: 1978.

Year Last Built: 1984.

Number Built: Approximately 160.

* Used to derive the design ratios referred to later in this article - here's how they're calculated...

Options & Alternatives

The Passport 40 offered at least two primary interior layouts, often referred to as the "A" and "B" plans or similar designations. These typically differed in the arrangement of the forward cabin and/or the main salon. For example, one layout might feature a pullman berth forward, while another might have a V-berth. The galley and navigation station arrangements also saw minor variations.

There were no direct "later versions" of the Passport 40 in the sense of a Passport 40 Mark II or a redesigned 40-foot model carrying the same name.

Robert Perry went on to design other Passport models, such as the Passport 42, 45, and 51, which were distinct designs with different specifications, even if they carried the "Passport" brand and shared some design philosophy (e.g., full foil keels, robust construction for offshore cruising).

These later models were not simply evolved versions of the Passport 40 but entirely new designs.

Sail Areas & Rig Dimensions

Sail Areas & Rig Dimensions

Sail Areas & Rig DimensionsSail Areas:

- Mainsail Area: Approximately 29.7m2 (320ft2)

- 100% Foretriangle Area: Approximately 50.2m2 (540ft2)

- Total Sail Area (Main + 100% Foretriangle): 79.9m2 (860ft2)

- Staysail Area: This varies significantly depending on the specific cut and size of the staysail but is typically much smaller than the genoa or mainsail.

Rig Dimensions:

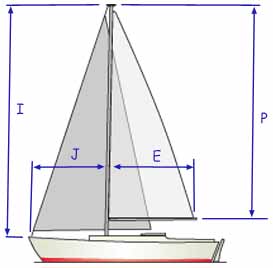

- I (Foretriangle height to masthead or hound): 16.46m (54.0 feet)

- J (Foretriangle base): 5.79m (19'0")

- P (Mainsail luff length): 14.63m (48'0")

- E (Mainsail foot length): 4.11m (13'6")

Published Design Ratios

The Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

- Sail Area/Displacement (SA/D) Ratio: Approximately 15.6

- Displacement/Length (D/L) Ratio: Approximately 280

- Ballast/Displacement (B/D) Ratio: Approximately 0.47 (47%)

- Capsize Screening Formula (CSF): Approximately 1.6

- Comfort Ratio (CR): Approximately 34.0

The design ratios of the Passport 40 paint a clear picture of a sailboat built for serious cruising, emphasizing comfort, stability, and robustness over raw speed. Let's break down what each ratio tells us:

1. Sail Area/Displacement (SA/D) Ratio (~15.6): This ratio tells us about the boat's power-to-weight. At around 15.6, the Passport 40 is a moderately powered vessel. It won't be the first to accelerate in light winds, but it has enough sail to move efficiently in a range of conditions.

It's designed for comfortable cruising, not racing, meaning it should perform well without being overly sensitive or demanding of its crew, especially in moderate breezes.

In strong winds, its cutter rig allows for easy reduction of sail, ensuring the boat remains manageable and not easily overpowered.

2. Displacement/Length (D/L) Ratio (~280): A D/L ratio of approximately 280 firmly places the Passport 40 in the heavy displacement category. This is a hallmark of a serious offshore cruiser. What does this mean for sailing characteristics?

- Comfortable Motion: Heavy displacement boats tend to cut through waves rather than bounce over them. This results in a smoother, more comfortable motion in a seaway, significantly reducing crew fatigue and seasickness on long passages.

- Robustness and Strength: High displacement often correlates with more substantial construction, indicating a durable and strong boat capable of handling challenging weather conditions.

- Load Carrying Capacity: You can load the Passport 40 with significant amounts of fuel, water, provisions, and gear for extended voyages without drastically impacting its performance or trim.

- Steady, Predictable Performance: While slower to accelerate and with a lower absolute top speed compared to lighter boats, its momentum carries it through lulls, providing a steady and predictable ride.

3. Ballast/Displacement (B/D) Ratio (~0.47 or 47%): A high B/D ratio of 47% signifies that a significant portion of the boat's weight is dedicated to ballast. This contributes directly to:

- High Initial Stability: The Passport 40 will be very stiff and resistant to heeling in light to moderate winds. This means a more upright boat, which is inherently more comfortable for the crew and easier to move around on deck and below.

- Excellent Sail Carrying Ability: With a high ballast ratio, the boat can carry its full sail plan effectively in stronger winds without excessive heel, allowing for efficient upwind performance.

- Enhanced Safety: A high B/D ratio significantly boosts the boat's ultimate stability and self-righting capability, a critical safety feature for offshore sailing.

4. Capsize Screening Formula (CSF) (~1.6): A CSF of 1.6 is well below the generally accepted offshore threshold of 2.0. This indicates a very high degree of resistance to capsize in rough seas. The formula considers the beam and displacement, and a lower number confirms that the Passport 40 is exceptionally stable and safe in extreme conditions.

5. Comfort Ratio (CR) (~34.0): This ratio specifically addresses the boat's motion comfort. A Comfort Ratio of approximately 34.0 places the Passport 40 firmly in the range of a "moderate bluewater cruiser".

This confirms that the boat's motion in a seaway will be predictable, relatively slow, and generally comfortable, even for extended periods at sea. This is a crucial factor for crew well-being and enjoyment on long passages, reinforcing the design's focus on practical cruising rather than exhilarating performance.

In summary, the design ratios collectively describe the Passport 40 as a heavy-displacement, exceptionally stable, and robust offshore cruising sailboat. It is engineered for safe, comfortable, and predictable passage making in a variety of conditions. While it won't be a speed demon, its design prioritizes crew comfort, load-carrying capacity, and seakindliness, making it an excellent choice for those seeking a reliable and well-mannered vessel for extended voyages.

But the Design Ratios are Not the Whole Story...

While design ratios like SA/D, D/L, B/D, Capsize Screening Formula, and the Comfort Ratio offer valuable insights into a sailboat's general character, relying solely on them to define its complete sailing characteristics presents several significant limitations. These ratios are simplified numerical representations of complex interactions, and here's why they can't tell the whole story:

Oversimplification of Hull Form and Hydrodynamics: Ratios are just numbers; they don't capture the actual shape of the hull below the waterline. Two boats could have identical D/L ratios, yet one might have a sleek, low-drag fin keel, while the other has a traditional full keel. This vastly impacts factors like upwind ability, maneuverability, turning radius, and light-air performance.

The distribution of volume within the hull, the fairness of the lines, and the efficiency of the keel and rudder foils—all crucial for how a boat truly sails—are entirely absent from these calculations. For instance, while a high Comfort Ratio suggests a comfortable motion, it doesn't describe how a particular hull shape handles a steep chop or a confused sea, which can vary greatly.

Ignores Dynamic Behavior and Seakindliness Nuances: Design ratios are static calculations. They tell us about theoretical stability or comfort at rest or in steady conditions, but they don't predict how a boat behaves dynamically in a living, constantly changing sea.

The rhythm of a boat's motion (pitch, roll, yaw), how it responds to sudden gusts, or its ability to shed waves off the bow are incredibly complex. A high Comfort Ratio, for example, suggests a slow, gentle motion, but it doesn't differentiate between a slow roll that feels pleasant versus a slow roll that feels ponderous or disorienting.

Actual seakindliness is a subjective quality influenced by many factors beyond simple dimensional ratios.

Doesn't Account for Rig Efficiency and Aerodynamics: While the SA/D ratio provides a total sail area, it doesn't describe the efficiency of the sail plan itself. This includes aspects like the aspect ratio of the sails (tall and narrow vs. short and wide), the efficiency of the mast and rigging (e.g., fractional vs. masthead rig), or the precise location of the sail's center of effort (CE) relative to the hull's center of lateral resistance (CLR).

These factors are critical for a boat's pointing ability, reaching speed, and overall balance under sail (i.e., how much weather or lee helm it carries). A good SA/D ratio doesn't guarantee a boat will sail well to windward if its rig is poorly designed for that purpose.

No Information on Construction Quality and Weight Distribution: Ratios use total displacement, but they don't reveal how that displacement is achieved or distributed. The quality of construction, the stiffness of the hull, and the placement of heavy components (engine, tanks, batteries) all significantly influence a boat's performance and motion.

A poorly built boat, even with theoretically good ratios, might flex excessively or have an uncomfortable motion due to poor weight distribution.

Ignores Ergonomics and Practicality: How easy is the boat to sail short-handed? Is the deck layout efficient for sail changes? Is the interior comfortable and functional at sea? These crucial practical considerations, which heavily influence a boat's "sailing characteristics" from an owner's perspective, are entirely absent from numerical ratios.

A boat with excellent ratios might be a nightmare to handle in a blow due to poor deck hardware or an awkward cockpit.

They're Guidelines, Not Guarantees: Ultimately, design ratios are best viewed as broad guidelines for categorizing a sailboat's general type and likely behavior. They can tell you if a boat is likely a racer or a cruiser, heavy or light. However, they cannot replace a thorough understanding of the specific design, a detailed review of hull lines, or, ideally, real-world experience sailing the boat.

A great designer can often create a boat that defies what the simple ratios might suggest, thanks to nuanced design choices.

In conclusion, while ratios like the Comfort Ratio are useful starting points for understanding a sailboat's theoretical characteristics, they offer a simplified view.

True sailing characteristics emerge from the holistic design package, including the intricate interplay of hull form, appendages, rig, construction, and the designer's specific intent.

More Specs & Key Performance Indicators for Popular Cruising Boats

This article was written with the assistance of Gemini, a large language model developed by Google. Gemini was used to gather information, summarize research findings, and provide suggestions for the content and structure of the article.

Recent Articles

-

Beneteau Oceanis 331 Clipper Review: Specs, Performance & Ratios

Feb 04, 26 07:25 PM

A comprehensive review of the Beneteau Oceanis 331 Clipper sailboat. We analyse design ratios, interior layout, and performance for prospective cruising owners. -

Self-Tacking Headsails: Track Systems vs Hoyt Jib Booms

Feb 03, 26 06:26 AM

Master the mechanics of self-tacking headsails. We compare traditional club-footed rigs, curved tracks, and the superior Hoyt Jib Boom for offshore sailing. -

Catalina 42 mk1 Review: Specs, Performance & Cruising Analysis

Feb 01, 26 06:35 AM

An in-depth review of the Catalina 42 mk1 sailboat. Explore technical specifications, design ratios, and practical cruising characteristics for this iconic cruiser.