- Home

- Electronics & Instrumentation

- Marine GPS System

Getting the Most From The Marine GPS System

In a Nutshell...

A marine GPS system constantly listens to signals from orbiting satellites to work out your boat’s position, speed and course over the ground – far more accurately and reliably than traditional methods ever could.

On this page I’ll explain in plain language how marine GPS works, what all those numbers on the display really mean, and which alarms (like anchor drag, off‑course and MOB) matter most to a cruising sailor.

We’ll also look at the pros and cons of handheld versus fixed units, how GPS ties into chartplotters, AIS and your wider electronics, and some simple habits that keep your system accurate and trustworthy offshore.

This page is part of our Boat Electronics on a Modern Cruising Sailboat hub. For an overview of all the main electronic systems on a modern cruising boat, see Boat Electronics on a Modern Cruising Sailboat.

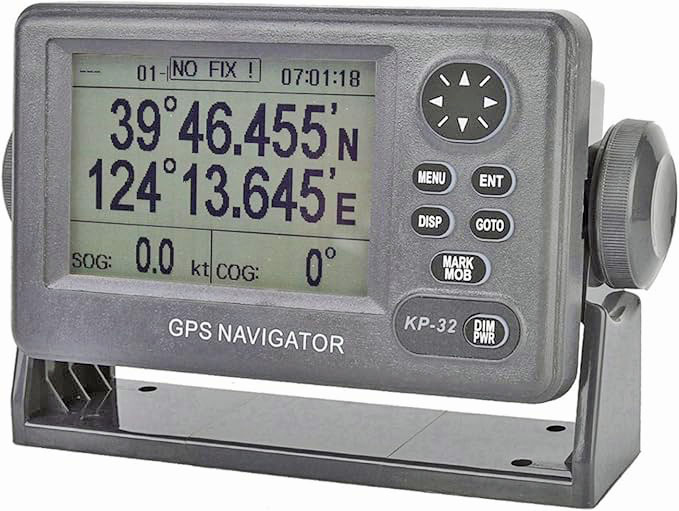

A fixed GPS Unit, showing an important warning

A fixed GPS Unit, showing an important warningTable of Contents

- How a Marine GPS System Works

- What Your Marine GPS Can Tell You

- GPS Alarms That Can Save Your Bacon

- Handheld vs Fixed GPS – and Why You Probably Want Both

- Integrating GPS With the Rest of Your Electronics

- Practical Tips for Reliable GPS Use Afloat

- What’s Next for Marine GPS

- Summing Up

- Frequently Asked Questions

How a Marine GPS System Works

Satellites, Signals and Your Boat’s Antenna

At the heart of modern marine navigation is the Marine GPS System, which is a network of 24 dedicated Global Positioning System (GPS) satellites spread out in geo-stationary orbit some 20,000km (12,500 miles) above the earth.

As the earth rotates below, at least four of the satellites are above the horizon at any one time and 'visible' from anywhere on earth.

Each of these navigational satellites knows precisely where it is, and kindly broadcasts this information at very accurately predetermined times to our boat's active GPS antenna.

From Signals to Position: Latitude, Longitude and Speed Over Ground

By recording the time it takes for these transmissions to reach the receiver, the system computes a three-dimensional fix. This provides your exact latitude, longitude, and altitude with a high degree of accuracy. Beyond a static position, the system calculates your 'Speed Over Ground' (SOG) by measuring the change in your position over time relative to the sea bed, providing a much more accurate representation of progress than traditional through-the-water speed logs.

What Your Marine GPS Can Tell You

As long as you give it a clue as to your intended route by entering a start and a destination waypoint, along with as many intermediate waypoints as may be required your GPS unit can perform a number of other useful tricks, including displays of:

Course, Cross Track Error and “Rolling Road” Displays

- Course Made Good (CMG) - the bearing from the starting point to the current position;

- Cross Track Error (XTE) - the distance off either side of the desired course, often shown on a 'rolling road' graphic;

ETA, Time on Route and Velocity Made Good

- Estimated Time of Arrival (ETA) - the date and time of arrival at the destination based on current speed over the ground;

- Estimated Time on Route - the time to go to arrival at the destination based on current speed over the ground;

- Ground Speed - the velocity in knots relative to the sea bed;

- Velocity Made Good (VMG) - the closing speed towards the destination.

The system goes beyond assisting with navigation—it also works as a vigilant safety tool.

GPS Alarms That Can Save Your Bacon

Your marine GPS unit can be a lifesaver, thanks to its alarm features. The Anchor Drag Alarm in particular will really get you out of your bunk in a hurry!

Anchor Drag and Off‑Course Alerts

The GPS unit serves as a vigilant digital watchkeeper. An anchor drag alarm allows you to set a small radius around your dropped anchor; if the boat moves outside this circle, a loud alert will sound—a feature that has saved many a skipper from an unexpected midnight grounding. Similarly, off-course alerts notify you immediately if the vessel’s Cross Track Error exceeds a preset limit, ensuring you don't wander into danger while distracted.

Arrival, Hazard and Lost‑Fix Warnings

As you approach your destination or a pre-identified hazard such as a reef or shoal, the system can trigger an arrival alarm. Equally important is the 'Lost-Fix' warning. If the antenna loses its view of the satellites or the signal is jammed, the unit will alert you that the displayed position is no longer reliable, prompting an immediate switch to manual navigation techniques.

The Man Overboard (MOB) Function and Drills

Every marine GPS includes a dedicated Man Overboard (MOB) button. Pressing this immediately stores the exact coordinates where the incident occurred and provides the helmsman with a clear, direct route back to that point. Because every second counts in a recovery situation, it is essential to conduct regular drills so that all crew members know how to activate this function instantly.

On the Water...

We were anchored in Simpson Bay, St Maarten. It was during the night (isn't it always) when a particularly nasty squall hit. The anchor alarm got us up and into the cockpit, where my befuddled brain could't understand why all the other boats were going passed us. And then the penny dropped...

If you’d like occasional deep‑dives on navigation electronics, GPS/chartplotters and real‑world cruising tips, you can join our free Sailboat Cruiser email list here:

Handheld vs Fixed GPS – and Why You Probably Want Both

For most sailors, the best approach is to carry both: a reliable fixed unit for regular navigation and a handheld unit stowed in an emergency grab bag.

Strengths and Limitations of Handheld Units

Handheld units are highly valued for their portability and independence. Because they often run on replaceable AA batteries and have their own internal antennas, they are completely independent of the boat’s electrical system. They are ideal for use in small tenders, for taking bearings from the cockpit, or as a primary navigation tool on very small vessels. However, their smaller screens can be harder to read in rough weather.

Fixed GPS Units at the Helm or Nav Station

Fixed units are the workhorses of offshore navigation. They are wired directly into the boat's 12v power supply and typically feature much larger, high-resolution screens that are easier to read in direct sunlight. These units are designed to be integrated with other instruments, providing a centralised display for all your navigational data.

Backup, Grab Bags and Redundancy for Cruisers

For most serious cruisers, the best strategy is a combination of both. A fixed unit serves as the primary tool for passage planning and daily navigation, while a handheld unit is kept in a waterproof 'grab bag'. In the event of a total electrical failure or the need to abandon ship, having a battery-powered GPS ensures you can still communicate your position and navigate to safety.

Integrating GPS With the Rest of Your Electronics

GPS and Chartplotters

While a basic GPS provides coordinates, a chartplotter overlays that data onto digital maritime charts. This integration allows you to see your vessel’s position relative to depth contours, buoys, and coastal features in real-time. To maintain accuracy, it is vital to keep your software and digital charts updated, as port layouts and buoy positions can change.

GPS, AIS and Small‑Boat Radar

Modern systems allow the GPS to work in tandem with the Automatic Identification System (AIS) and radar. This provides a comprehensive 'situational awareness' picture, where you can see the name, speed, and heading of nearby vessels overlaid on your map. High-end systems can even include real-time weather overlays and sonar data to map the seabed, helping you avoid underwater hazards when you're looking for somewhere to drop the hook.

Linking GPS to GMDSS and Distress Systems

One of the most significant safety advancements is linking the GPS to the Global Maritime Distress and Safety System (GMDSS). When connected to a Digital Selective Calling (DSC) VHF radio, your GPS coordinates are automatically sent if you trigger a distress alert. This ensures that rescue authorities know exactly where to look without you having to speak a word over the radio.

Practical Tips for Reliable GPS Use Afloat

Keeping Charts and Software Up to Date

Outdated systems may not account for newly marked hazards or changes in harbour regulations. Regularly check the manufacturer’s website for firmware updates and ensure your electronic charts are the latest versions. This not only improves safety but often adds new features and better processing speeds to your device.

Power Supply, Antenna Placement and Basic Maintenance

Ensure your GPS antenna has a clear, unobstructed view of the sky, away from large metal masts or radar scanners that might cause interference. Regularly inspect and clean electrical connections to prevent corrosion from salt air. Modern units also include security features such as PIN protection and anti-theft algorithms to detect signal spoofing; ensure these are activated if you are sailing in high-risk areas.

Always Backing Up with Traditional Navigation Skills

Despite the reliability of modern electronics, they can fail due to lightning strikes, battery depletion, or signal jamming. A prudent navigator always maintains a paper chart and basic traditional skills. Use your GPS as your primary tool, but verify your position occasionally using landmarks or a compass to ensure you remain confident in your location should the screens go dark.

What’s Next for Marine GPS

Multi‑Constellation GNSS (GPS, Galileo, BeiDou, etc.)

The future of marine navigation lies in Multi-Constellation Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS). Rather than relying solely on the American GPS network, modern receivers can now track European (Galileo), Russian (GLONASS), and Chinese (BeiDou) satellites simultaneously. This results in significantly higher accuracy—often down to a few centimetres—and much better redundancy.

Simple Connectivity and App Integration for Cruisers

We are seeing a move towards seamless wireless connectivity and cloud integration. This allows sailors to plan routes on a tablet at home and sync them to the boat's instruments automatically. Furthermore, the 'Internet of Things' (IoT) is beginning to allow GPS units to monitor onboard systems remotely, alerting owners to issues like low battery voltage or bilge pump activation via smartphone apps.

Summing Up

The marine GPS has evolved from a simple coordinate-fixing device into a sophisticated command centre. By understanding how to interpret data like Cross Track Error and VMG, and by utilising integrated safety features like AIS and GMDSS, sailors can navigate with unprecedented confidence. However, the technology is most effective when supported by regular maintenance, software updates, and a solid foundation in traditional seamanship.

This article was written by Dick McClary, RYA Yachtmaster and author of the RYA publications 'Offshore Sailing' and 'Fishing Afloat', member of The Yachting Journalists Association (YJA), and erstwhile member of the Ocean Cruising Club (OCC).

Frequently Asked Questions

How many satellites does a marine GPS need for a fix?

How many satellites does a marine GPS need for a fix?

A minimum of three satellites is required for a two-dimensional position (latitude and longitude), but a fourth is necessary to provide altitude and a highly accurate three-dimensional fix.

What is the difference between GPS and GNSS?

What is the difference between GPS and GNSS?

GPS specifically refers to the American Global Positioning System. GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System) is the umbrella term for all satellite networks, including Galileo (EU), GLONASS (Russia), and BeiDou (China).

Can a marine GPS work without an internet connection?

Can a marine GPS work without an internet connection?

Yes. GPS relies on radio signals directly from satellites, not cellular data or Wi-Fi. However, internet connectivity is often needed for downloading software updates or syncing cloud-based routes.

Is a handheld GPS as accurate as a fixed unit?

Is a handheld GPS as accurate as a fixed unit?

Generally, yes. The internal technology and signal processing are very similar. The main differences lie in screen size, power source, and the ability to integrate with other onboard electronics like autopilot or radar.

What should I do if my GPS loses its signal?

What should I do if my GPS loses its signal?

Immediately note your last known position on a paper chart. Revert to traditional navigation using your compass, depth sounder, and visual landmarks (dead reckoning) until the signal is restored or you reach safety.

Recent Articles

-

CSY 44 Sailboat: Comprehensive Review, Specs & Performance Analysis

Feb 22, 26 10:41 AM

An in-depth review of the CSY 44 sailboat. Discover technical specifications, design ratios, and why this heavy-displacement cruiser remains a top choice for ocean voyagers. -

Irwin 54 Sailboat: Comprehensive Review, Specs & Performance Analysis

Feb 22, 26 07:24 AM

An expert review of the Irwin 54 sailboat. Explore technical specifications, design ratios, cruising capabilities, and why this shoal-draft yacht is a liveaboard favourite. -

Beneteau Oceanis 473 Review: Specs, Performance & Cruising Guide

Feb 20, 26 04:49 AM

An in-depth review of the Beneteau Oceanis 473. Discover technical specifications, design ratios, and why this Groupe Finot design remains a top offshore cruising choice.