- Home

- Electronics & Instrumentation

- Gmdss System

GMDSS for Offshore Sailors

The Complete Safety and Comms Guide

Key Takeaways...

Modern GMDSS (Global Maritime Distress & Safety System) for offshore sailors is a multi-layered digital safety net that ensures you are never truly alone. By integrating Digital Selective Calling (DSC), satellite communications, and automated Maritime Safety Information (MSI), the system replaces unreliable manual watches with instant, data-rich alerts. While high-speed tools like Starlink offer superb connectivity for daily life, they remain secondary to the regulated, battle-hardened reliability of the GMDSS framework for emergency response and rescue coordination.

The key components of the Global Maritime Distress & Safety System (GMDSS)

The key components of the Global Maritime Distress & Safety System (GMDSS)Table of Contents

- The Evolution of Maritime Safety

- Core Components of the GMDSS Infrastructure

- Sea Areas & Your Yacht: Mapping Your Risk

- DSC & MMSI: The Digital Handshake

- EPIRBs & SARTs: Your Last Line of Defence

- MSI & NAVTEX: Receiving Critical Warnings

- Satellite Comms: Inmarsat, Iridium, & the Starlink Paradigm

- Legal Requirements & Certification for Leisure Craft

- Integrating GMDSS with Modern Boat Electronics

- Installation & Maintenance Protocols

- Summing Up

- Frequently Asked Questions

The Evolution of Maritime Safety

For decades, the safety of a vessel at sea relied on the "aural watch." A radio officer or bridge officer sat with headphones, listening for a faint voice or Morse code signal through the static of atmospheric interference. This system was inherently flawed, limited by human fatigue, signal propagation, and the sheer vastness of the horizon.

The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) recognised these limitations and spearheaded the GMDSS. The goal was simple yet ambitious: to automate the distress process. On 1 February 1999, the mandatory listening watch on 2182kHz for SOLAS ships ended. By 2005, the VHF Channel 16 watch also transitioned. Today, the system relies on digital "handshakes" and satellite pings, ensuring that a distress alert is received and acknowledged even if the crew is unable to speak.

Core Components of the GMDSS Infrastructure

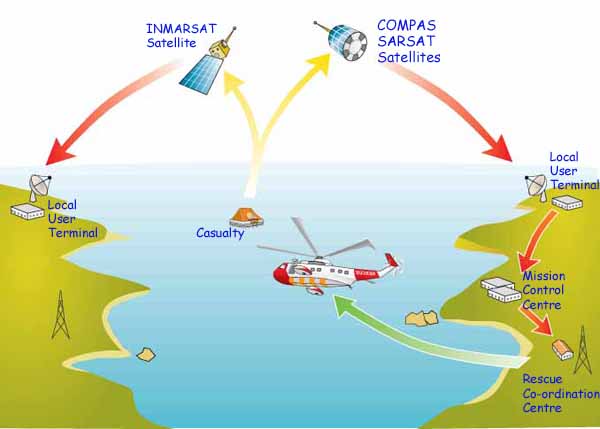

GMDSS is not a single piece of hardware but a "system of systems." For the offshore sailor, this infrastructure provides three critical functions: alerting, search and rescue coordination, and the dissemination of Maritime Safety Information (MSI).

The architecture relies on both terrestrial and satellite technologies. Terrestrial systems use VHF, MF, and HF radio bands, while satellite systems, primarily overseen by Inmarsat and Cospas-Sarsat, provide global coverage. Each component is designed with redundancy in mind. If your VHF cannot reach a shore station, your EPIRB alerts a satellite. If the satellite link is obscured, your NAVTEX receiver provides the local weather warning you missed on the broadcast.

Sea Areas & Your Yacht: Mapping Your Risk

The equipment you are required (or advised) to carry depends entirely on your "Sea Area." These are not geographical zones like countries, but rather definitions based on the range of shore-based communication services.

| Sea Area | Description & Range | Primary Technology |

|---|---|---|

| Area A1 | Within VHF coverage of a coast station (20–30nm) | VHF DSC |

| Area A2 | Within MF coverage of a coast station (approx. 100nm) | MF DSC |

| Area A3 | Within the coverage of Inmarsat satellites (70°N to 70°S) | Satcom or HF DSC |

| Area A4 | The Polar regions (beyond 70° latitude) | HF DSC with NBDP |

For the typical blue-water cruiser crossing the Atlantic or Pacific, you are operating in Sea Area A3. This necessitates a shift in mindset from simple VHF to a combination of satellite-based alerting and potentially High Frequency (HF) radio.

DSC & MMSI: The Digital Handshake

Digital Selective Calling (DSC) is the most significant advancement in maritime radio. It allows you to send a digital data burst to another vessel or a shore station. This burst contains your Maritime Mobile Service Identity (MMSI), a unique nine-digit number that acts like a telephone number for your boat.

When you press the red "Distress" button, the radio automatically broadcasts your MMSI and, if interfaced with a GPS, your exact coordinates and the nature of the distress. This removes the "human error" factor of trying to read coordinates over a radio in a sinking boat. Crucially, DSC radios also act as a "pager," allowing you to call a specific ship without broadcasting to everyone on the channel.

EPIRBs & SARTs: Your Last Line of Defence

When all else fails and you must abandon ship, the Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon (EPIRB) is your lifeline. These units operate on the 406MHz frequency, sending a signal to the Cospas-Sarsat satellite constellation.

Modern EPIRBs now often include an AIS-SART (Search and Rescue Transponder) component. While the 406MHz signal tells the world where you are, the AIS-SART shows your precise location on the chartplotters of nearby vessels. This is a game-changer for local recovery. Traditional Radar SARTs are still common on commercial ships, showing as a line of twelve dots on a radar screen, but for leisure yachts, AIS-based recovery is rapidly becoming the standard due to its integration with modern navigation displays.

MSI & NAVTEX: Receiving Critical Warnings

Safety is as much about avoidance as it is about rescue. The Maritime Safety Information (MSI) system provides navigational warnings, meteorological forecasts, and urgent safety messages.

NAVTEX is the primary tool for this in coastal and offshore waters (up to 400nm). It is a small, low-cost receiver that prints or displays text messages on 518kHz. Because it is a "pull" technology, you don't need to be listening at a specific time; the messages are stored for you to read at your convenience. For those heading further afield, these same messages are broadcast via the SafetyNET service over satellite.

Satellite Comms: Inmarsat, Iridium, & the Starlink Paradigm

he satellite landscape is changing rapidly. For decades, Inmarsat was the only game in town for GMDSS. It remains the gold standard for reliability and is integrated into the formal rescue infrastructure. However, Iridium’s "Certus" service has recently been approved for GMDSS, offering truly global coverage, including the poles.

Then there is Starlink. Many offshore sailors are now opting for Starlink Maritime for its high speeds and low latency. It is excellent for downloading GRIB files and keeping the crew happy with Netflix. However, it is vital to remember that Starlink is a commercial internet service, not a regulated safety system. It does not have the same "priority" protocols as GMDSS satellite systems, which ensure that a distress message always gets through regardless of network congestion.

Iridium vs Starlink: The Safety vs Speed Debate

The debate on the pontoon usually pits the high-speed data of Starlink against the global reliability of Iridium. While Starlink has revolutionised life at sea by allowing for video calls and seamless weather downloads, it operates on a "best effort" commercial basis. This means in times of network congestion or system maintenance, your data is not guaranteed.

Iridium, particularly the GMDSS-approved Certus service, operates on a different philosophy. It is designed for 99.9% uptime and features "pre-emption" protocols. This ensures that if you trigger a distress alert, the system will literally drop other people’s non-essential data calls to ensure your signal reaches a Rescue Coordination Centre. For the offshore sailor, the ideal setup is not "either/or" but rather using Starlink for the heavy lifting and Iridium for the critical, unshakeable safety link.

Legal Requirements & Certification for Leisure Craft

While SOLAS regulations primarily target commercial ships over 300 gross tonnes, leisure craft are subject to national regulations. In the UK, for example, the RYA oversees the Short Range Certificate (SRC), which is a legal requirement for anyone operating a DSC-equipped radio.

If you are heading offshore, the Long Range Certificate (LRC) is highly recommended. This covers MF and HF radio operations and satellite communications. Furthermore, you must ensure your ship’s radio licence is up to date and correctly lists all your equipment, including your EPIRB HEX ID and your MMSI.

Integrating GMDSS with Modern Boat Electronics

For the modern navigator, GMDSS equipment should not exist in a silo. Your VHF, AIS, and GPS should all be interconnected, typically via an NMEA 2000 network. This ensures that when you hit the distress button, the radio has the most accurate position data available.

When planning your system, consider how these components sit within your wider electrical architecture. High-draw items like HF radios require robust power management, while sensitive receivers like NAVTEX need careful antenna placement to avoid interference from LED lighting or solar controllers. For a deeper dive into how these systems fit together, you might want to look at our comprehensive guide on Boat Electronics on a Modern Cruising Sailboat, which covers the physical installation and networking of these vital tools. Integrating your safety gear into a cohesive network allows for better situational awareness and faster response times in an emergency.

Installation & Maintenance Protocols

The best safety equipment in the world is useless if the batteries are dead or the antenna cable is corroded. Maintenance is a critical pillar of GMDSS.

- EPIRB Testing: Use the "self-test" function monthly. Check the expiry date of the battery and the hydrostatic release unit (HRU) every season.

- DSC Check: Perform a "DSC Test Call" to a shore station or a buddy boat. Do not use the distress button for testing.

- Antenna Integrity: Check all PL-259 connectors for signs of green corrosion or water ingress, which can cripple your transmit power.

- Battery Redundancy: Ensure your emergency comms can run off an isolated battery bank if the main engine room is flooded.

Summing Up

Navigating the complexities of GMDSS for offshore sailors requires a balance of traditional seamanship and technical proficiency. By understanding the sea areas you intend to traverse and equipping your vessel with the appropriate DSC, satellite, and MSI tools, you significantly tilt the odds in your favour should the unthinkable happen. Remember that while modern internet solutions provide comfort and convenience, the GMDSS framework is the only system globally recognised and legally mandated to protect lives at sea. Treat your safety electronics with the same respect as your rig or your hull, and they will not let you down when the horizon turns grey.

This article was written by Dick McClary, RYA Yachtmaster and author of the RYA publications 'Offshore Sailing' and 'Fishing Afloat', member of The Yachting Journalists Association (YJA), and erstwhile member of the Ocean Cruising Club (OCC).

Frequently Asked Questions

Do I really need a Long Range Certificate (LRC) for blue-water cruising?

Do I really need a Long Range Certificate (LRC) for blue-water cruising?

If your vessel is equipped with an MF/HF radio or a GMDSS-approved satellite terminal (like Inmarsat C), then yes, an LRC is legally required. Even if not strictly enforced in every jurisdiction, the knowledge gained regarding signal propagation and satellite protocols is invaluable for offshore safety.

Can I use an AIS-MOB device instead of an EPIRB?

Can I use an AIS-MOB device instead of an EPIRB?

No. They serve different purposes. An EPIRB alerts the global SAR network via satellite. An AIS-MOB device alerts nearby vessels using VHF frequencies. For a short-handed offshore crew, an AIS-MOB is excellent for local recovery, but you still need an EPIRB for the "big picture" rescue.

Is it okay to test my DSC distress button to see if it works?

Is it okay to test my DSC distress button to see if it works?

Absolutely not. Triggering a DSC distress alert without a genuine emergency can launch an expensive and dangerous international rescue operation. Use the "test call" feature in the radio menu to send a digital ping to a specific MMSI instead.

Does Starlink satisfy the GMDSS requirements for a coded vessel?

Does Starlink satisfy the GMDSS requirements for a coded vessel?

Currently, no. For vessels required to meet SOLAS or commercial coding standards, Starlink is considered "additional equipment." It does not yet meet the rigorous "always-on" and "priority access" standards required for a primary GMDSS distress alerting system.

Why does my NAVTEX get so much "garbage" text in the messages?

Why does my NAVTEX get so much "garbage" text in the messages?

This is usually caused by signal interference or a weak signal. Because NAVTEX uses low-frequency radio, it is sensitive to "electrical noise" from onboard electronics like LED drivers, battery chargers, or even the computer you are using. Improving antenna height and shielding can help.

Recent Articles

-

Jeanneau Voyage 12.50 Review: Blue-Water Performance & Buyer's Guide

Mar 01, 26 06:05 PM

A detailed review of the Jeanneau Voyage 12.50 sailboat. Discover technical specs, performance ratios, and a buyer's checklist for common problem areas. -

CSY 44 Sailboat: Comprehensive Review, Specs & Performance Analysis

Feb 22, 26 10:41 AM

An in-depth review of the CSY 44 sailboat. Discover technical specifications, design ratios, and why this heavy-displacement cruiser remains a top choice for ocean voyagers. -

Irwin 54 Sailboat: Comprehensive Review, Specs & Performance Analysis

Feb 22, 26 07:24 AM

An expert review of the Irwin 54 sailboat. Explore technical specifications, design ratios, cruising capabilities, and why this shoal-draft yacht is a liveaboard favourite.