- Home

- Cruising Sailboats

- Qualities of Offshore Sailboats

Offshore Sailboat Qualities

In a Nutshell...

Getting to grips with the qualities of offshore sailboats is all about understanding that a vessel’s suitability for a long passage is a delicate balance of design, technology, and sheer grit. Beyond a boat’s basic seaworthiness, it comes down to how it handles the open ocean, how comfortably it treats its crew, and whether it’s equipped with the right gear to get you through the rough patches. As an experienced sailor, I can tell you that a boat you can trust is more than just a boat—it's your sanctuary at sea, and it’s a direct extension of your own experience and preparation.

With the right crew and equipment aboard, this Rustler 42 cutter is an eminently seaworthy offshore cruising boat.

With the right crew and equipment aboard, this Rustler 42 cutter is an eminently seaworthy offshore cruising boat.Table of Contents

Perhaps we should first try to define exactly what offshore sailboats are. Clearly, they’re a step up from boats designed for inshore sailing, but what’s the difference between inshore and offshore sailing?

Well, if we can agree that inshore sailing means a coastal passage where the sailboat is always within six hours of a safe haven—six hours being the 'imminent' time period in the Shipping Forecast—then it’s fair to say that offshore sailing starts where inshore sailing leaves off.

The European Commission’s Recreational Craft Directive (RCD) has something to say about offshore sailboats too. It requires that offshore sailboats shall be designed for sea conditions up to Beaufort F8 (wind speeds of 34 to 40 knots) and Significant Wave Heights up to 4m. Since the Significant Wave Height is the average of the highest 30% of all waves, and as individual waves can be twice that, it’s clear that offshore sailing is not for the faint-hearted or inadequately prepared.

But with a little luck, pretty much any reasonably sized cruising sailboat can make an offshore passage, even cross an ocean. And many do, but luck—an unreliable commodity with a tendency to run out altogether—isn’t a sound basis upon which to plan such a venture. In challenging circumstances, and with little prospect of outside assistance, an offshore sailor must have confidence in the seaworthiness of the vessel beneath their feet.

But this doesn’t mean, as more than a few cruising sailors will have you believe, that only heavy displacement vessels make good offshore sailboats. Overweight, under-canvassed tubs that refuse to sail much closer to the wind than a beam reach and need half a gale to get going at all, do not make ideal offshore sailboats in my view. Sailing performance that gives a sailboat the capacity to reach a safe haven before a storm arrives, together with the close-winded ability to beat off a lee shore to the safety of deep water, are desirable characteristics indeed.

So Just What Should We Look for in Offshore Sailboats?

Irrespective of whether the sailboat is constructed of GRP, steel, aluminium, wood, or ferrocement, or whether it’s heavy or light displacement, or a monohull or multihull, the following three characteristics are fundamental to its suitability as an offshore sailboat.

Seaworthiness

Seaworthiness is a difficult concept to define precisely; many will correctly argue—your insurance company included—that it isn’t just about the sailboat. Crew strength and experience are clearly influencing factors, as is the extent of stores and equipment carried aboard. The whole endeavour must be ‘fit for purpose’. But let’s settle on a narrower definition. How about a seaworthy boat is one that’s capable of looking after her crew in all but extreme conditions?

While few boats venturing offshore will ever experience extreme heavy weather unless they go looking for it, it must be said that in such conditions the greatest danger is of being rolled over by a breaking wave. The ability to resist this alarming prospect is clearly high on the list of seaworthy attributes. The height of a breaking wave capable of capsizing a boat is directly proportionate to the size of the boat, so a good big offshore sailboat is always more seaworthy than a good small one.

So, seaworthiness can’t be described in absolute terms but, in all regards other than size, it’s a function of design. Structural and watertight integrity are fundamental, and in addition to the ability to stay afloat, she must have the windward ability to manoeuvre clear of danger in heavy weather. She must also be able to provide shelter for her crew, and to recover quickly from a knockdown. Performance then, and comfort, are part of seaworthiness.

A quick note on monohulls versus multihulls: while a monohull's heavy keel gives it the ability to self-right after a knockdown, a modern multihull is designed for incredible stability and buoyancy. Catamarans, for example, have a very wide beam and rarely heel, which makes for a much more comfortable ride and reduces the risk of seasickness. They can't self-right if they flip, but their positive buoyancy means they will stay afloat, providing a potential place of refuge. The choice between the two is really a matter of trade-offs, balancing the monohull's proven self-righting capability against the catamaran's superior comfort and space.

Performance

There’s no real argument in favour of slow offshore sailboats—after all, you can sail a quick sailboat slowly, but you can’t sail a slow sailboat quickly. The advantages of sailing quickly are clear, and were brought home to me during a passage from Portugal to Madeira, a distance of 480-odd nautical miles. The internet forecast was for favourable conditions so we planned on a passage time of 80 hours at our usual 6 knots boat speed. We left Portimão on the Algarve shortly after dawn along with another sailboat, agreeing to keep in touch on the VHF and planning to arrive together around midday on the fourth day. She was about the same length overall as us but with pretty little overhangs at each end instead of our rather plumb bow and stern.

250 miles out, our rather clunky first generation GPS told us we were at 0.00°N and 0.00°W and no amount of tapping and tweaking either at the instrument or the antenna end would persuade it to say otherwise. The NAVTEX and the barometer were now suggesting that the internet forecast ashore was on the optimistic side, and we could expect things to get worse, which they rapidly did. I remember getting one sunsight in before the sun became but a lighter patch in a dark sky and the true horizon was lost in a series of approaching wave crests. Now reduced to dead-reckoning, and with the other sailboat left astern and out of VHF range, I was concerned that we may be on our Atlantic crossing a little earlier than anticipated.

Fortunately, the island of Porto Santo appeared pretty much where it should have done, and in the worsening conditions we ducked into the sheltered harbour, much relieved. But the point of this little tale is that the other, slower sailboat spent a further two nights at sea, hove-to in awful conditions. We met them ashore sometime later—Mary and I looking for a new GPS and our friends trying to find a sailmaker. Our conversation centred around what a difference a knot or two makes.

A Crucial Component: The Rig & Sails

You can have the most seaworthy hull in the world, but without a strong, reliable rig and a sail plan to match, you're not going anywhere. The rig is the engine of your boat and the component that is under the most stress on an offshore passage. A solid rig, correctly tuned and well-maintained, is paramount.

For offshore sailing, many sailors prefer a fractional rig, which allows for better control over mainsail shape and reduces the load on the mast, though masthead rigs are also a proven choice. What's more important than the type of rig is its condition—the standing and running rigging must be in excellent shape.

Your sail inventory is equally critical. You’ll need a robust mainsail and a working jib, but also a dedicated storm jib and a trysail. These smaller, stronger sails are designed for use in heavy weather and can be the difference between getting through a gale safely and breaking a mast or tearing a larger sail. A well-equipped boat will also carry a variety of headsails for different wind conditions, allowing you to maintain speed and comfort throughout the passage. In my view, a full sail wardrobe is a small price to pay for confidence out on the water.

Seakindliness

While a boat’s seaworthiness is its ability to stand up to heavy weather without breaking apart, its seakindliness is a measure of how comfortably it does so. Nothing endears a boat more to its crew than the way it handles in a seaway. A seakindly motion reduces crew fatigue and seasickness, turning what could be a miserable passage into a manageable one. For example:

- Offshore sailboats should be easy on the helm and be capable of being trimmed to provide a small degree of weather helm. Those that heel alarmingly and gripe up in every gust—leaving the helmsman no option but to dump the main in a hurry—are a nightmare.

- Offshore sailboats should have good directional stability. A sailboat that can be left to sail herself for a few moments whilst the helmsman puts the kettle on, is a great boon. Such a sailboat will respond well to a windvane self-steering system or draw the minimum current from an autopilot.

- Offshore sailboats should be responsive to the helm under both sail and power. A sailboat should be capable of tacking up a narrow channel or a river to her mooring, and wriggling in and out of tight marina berths under power.

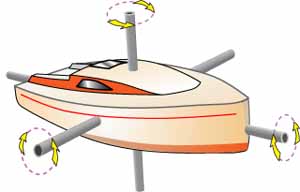

But not only must offshore sailboats handle well, they must also have a comfortable, easy motion underway. As we saw earlier when discussing stability and righting moment, a boat rotates around three axes. The combined effect of this movement together with forward motion, and taken as the locus of a single point, is a distorted helix. Not surprising then, that some of us can feel a little queasy at times.

The three axes of rotation—pitch, roll and yaw

The three axes of rotation—pitch, roll and yawIt’s not only the magnitude of these movements that causes the problem—much of the discomfort is caused by the angular rate of change. Take the roll motion, for example, which probably has the most profound effect on crew comfort and fatigue. It’s not just the extent of the roll angle, but the period of the roll and the ‘jerkiness’ experienced at the ends of the roll. This jerkiness, the roll acceleration, is the force that’s likely to throw you off balance and is the primary culprit in inducing seasickness.

Size of course, has much going for it as far as seakindliness is concerned, as the bigger the offshore sailboat the less inclined it is to leap about.

Crew Comfort & Ergonomics

When you're a long way from home, your sailboat isn’t just a vessel—it’s your home, your office, and your lifeline. A boat that is well-designed for a crew's comfort and efficiency can make all the difference between a miserable passage and a successful one. While performance and seaworthiness are crucial, the ergonomics of the interior and exterior are just as important for maintaining morale and reducing fatigue on long passages.

Inside, a proper offshore galley is more than just a place to cook; it’s a secure workspace where you can prepare a hot meal in a seaway. Look for a gimballed stove, plenty of handholds, and a layout that allows you to brace yourself safely. The navigation station needs to be a dedicated, secure space where you can work with charts and electronics without being thrown about. Equally important are the sea berths—they should be comfortable and positioned low down, with lee cloths to hold you securely in place, allowing you to get some proper rest.

Outside, the cockpit is your main hub. It should be deep and self-draining, with high coamings to offer protection from waves. The rig control lines and sheets should be led to the cockpit, so you don't have to go on deck in rough weather. Small details like well-placed lockers for gear storage and a secure spot to tether your safety harness can make a world of difference. An efficient and comfortable boat is one you can operate with minimum effort, leaving you with more energy for the passage itself.

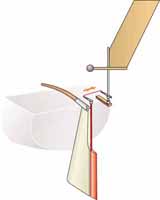

The Art of Self-Steering

On any long passage, a reliable self-steering system is a non-negotiable piece of equipment. Without it, you’ll be on the helm all day, every day, which is simply not sustainable.

You really have two main choices: a windvane or an autopilot. An autopilot is an electronic brain that steers the boat to a set compass course. They’re excellent in light winds or when motoring and can even steer to an apparent wind angle. However, they consume a lot of electricity, which is a concern on a long voyage.

A windvane, on the other hand, is a mechanical marvel that steers the boat relative to the wind. It requires no electricity whatsoever. While it might not be as precise as an autopilot, it is incredibly reliable and a favourite of seasoned long-distance cruisers.

A simple windvane self-steering gear

A simple windvane self-steering gearMy advice? Don’t choose one over the other; choose both. An autopilot for short hops and motoring, and a windvane for the long-distance stuff. Having a primary windvane with a well-maintained autopilot as a backup system is the gold standard for offshore sailing. Redundancy is key when you're thousands of miles from the nearest chandlery.

Beyond the Boat: Modern Technology & Essential Equipment

As you think about a boat's design qualities, you also need to consider the technology that makes offshore passages safer and more comfortable. From my own experience, a well-equipped boat can make all the difference, especially when you’re a long way from home.

Here are a few modern essentials I wouldn’t leave shore without:

- Navigation & Communication: Today's sailors rely on more than just a sextant. A good GPS system is non-negotiable, but having a secondary system, maybe a handheld unit, is crucial for redundancy. A VHF radio is standard, but having a satellite phone or SSB (Single Side Band) radio for long-range communication gives you real peace of mind. The Automatic Identification System (AIS) is also a game-changer, allowing you to see other vessels and be seen, significantly reducing the risk of collision, particularly at night or in poor visibility.

- Power & Water: On a long passage, you can’t just plug in. Modern sailboats are increasingly using renewable energy. Solar panels are a fantastic way to keep your batteries topped up and power things like your autopilot, fridge and navigation electronics. A watermaker is also a huge asset, giving you the freedom to make your own fresh water rather than worrying about tank capacity.

- Safety Gear: While some of this is required by law, good practice goes beyond the bare minimum. A 406 MHz EPIRB (Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon) and a PLB (Personal Locator Beacon) are essential for alerting rescue services in an emergency. A self-inflating lifejacket with a built-in light and harness, along with a grab bag containing emergency supplies and key documents, is the final line of defence.

Summing Up

Ultimately, the qualities of offshore sailboats are not just about a list of technical specs or a designer's grand plan. It’s about a vessel that you can trust to carry you safely through whatever the ocean throws at you. A boat with good performance, a seakindly motion, and inherent seaworthiness is a joy to sail and a home you can feel secure in. For a broader perspective on what makes any boat a great vessel, regardless of its intended use, be sure to read our comprehensive guide on The Essential Features of All Good Cruising Sailboats.

My advice? Don’t get hung up on a specific brand or a particular displacement. Instead, look for a boat that feels right for you, one that inspires confidence and seems as keen to get across the ocean as you are.

This article was written by Dick McClary, RYA Yachtmaster and author of the RYA publications 'Offshore Sailing' and 'Fishing Afloat', member of The Yachting Journalists Association (YJA), and erstwhile member of the Ocean Cruising Club (OCC).

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the best type of keel for offshore sailing?

What is the best type of keel for offshore sailing?

There is a lot of debate about this, but for offshore sailing, a full or long keel often provides great directional stability and offers some protection to the rudder. However, a modern fin keel with a spade rudder can offer superior performance and manoeuvrability. The best choice depends on the specific design and the sailor’s preference for stability versus speed.

How important is a boat's age for offshore sailing?

How important is a boat's age for offshore sailing?

A boat's age is less important than its condition and how well it has been maintained. Many older, well-built vessels are excellent offshore boats, often with stronger construction and more traditional designs. What matters most is a thorough survey, a solid refit plan, and continuous maintenance to ensure all systems are reliable.

Should I choose a monohull or a multihull for an ocean crossing?

Should I choose a monohull or a multihull for an ocean crossing?

Monohulls are a classic choice for offshore passages and are known for their ability to self-right. Multihulls offer great stability, speed and living space, but require different sailing techniques and have a higher initial cost. The decision is personal and depends on your budget, cruising style and comfort preferences.

What are some of the most common mistakes people make when choosing an offshore sailboat?

What are some of the most common mistakes people make when choosing an offshore sailboat?

Many people get caught up in either the latest fashion or the idea that only a certain type of boat will do. Common mistakes include buying a boat that’s too large and complex for them to handle or maintain, prioritising speed over a comfortable motion, or not accounting for the cost of outfitting a boat for a long passage.

What is the minimum size for an offshore sailboat?

What is the minimum size for an offshore sailboat?

While there is no official minimum, most experienced sailors would suggest a boat in the 30-foot range is a good starting point. Smaller boats have successfully crossed oceans, but a slightly larger vessel provides more comfort, storage capacity and the ability to carry a wider range of equipment, which is a great asset on a long passage.

Recent Articles

-

Dufour 470 Review: Specs, Ratios & Expert Performance Analysis

Feb 12, 26 11:25 AM

An in-depth review of the Dufour 470 sailboat. Explore technical specifications, design ratios, and cruising characteristics of this versatile Umberto Felci design. -

Island Packet 40 Review: Specs, Performance & Cruising Analysis

Feb 09, 26 05:05 AM

An in-depth review of the Island Packet 40 sailboat. Explore technical specifications, design ratios, and real-world cruising performance for this legendary blue-water cruiser. -

Beneteau Oceanis 331 Clipper Review: Specs, Performance & Ratios

Feb 04, 26 07:25 PM

A comprehensive review of the Beneteau Oceanis 331 Clipper sailboat. We analyse design ratios, interior layout, and performance for prospective cruising owners.