Mastering Your Roller Furling Headsail: A Guide to Jibs & Genoas

In a Nutshell

Roller furling jibs and genoas have become a godsend for cruising sailors, letting us adjust sail area from the safety of the cockpit. Keeping your system in top shape is essential for this convenience, so regular checks on the forestay, bearings, and furling line are a must. A little bit of knowledge about sail trim and rig tension goes a long way, too. Plus, you’ll want to get to grips with a few simple tricks to prevent common foul-ups and keep everything running smoothly.

Larger boats are likely to sport an electric or hydraulic headsail furler

Larger boats are likely to sport an electric or hydraulic headsail furlerTable of Contents

- Why Roller Furling Is a Cruising Sailor's Best Friend

- Getting to Grips With Maintenance

- Tuning Your Rig & Sail for Optimal Performance

- Reefing in Different Conditions

- Avoiding Roller Reefing Foul-Ups

- Emergency Procedures

- Adjusting the Sheeting Angle

- Other Headsail Considerations

- Summing Up

- Frequently Asked Questions

Why Roller Furling Is a Cruising Sailor's Best Friend

Like most cruising sailors, I'm a big fan of the roller furling jib. Not only are they a convenient way of getting the jib out of the way at the end of a passage, they enable us to easily adjust the headsail area to suit the prevailing conditions without having to leave the cockpit.

It’s true that a partially furled genoa will never be quite as efficient as a hanked-on jib of the same size, but for the cruising sailor, that small performance loss is more than balanced by the sheer convenience and safety that these systems offer.

Some gung-ho types might revel in changing hanked-on foresails in the dark on a pitching foredeck in a rising gale. Not me. Never did, come to think of it—and don't know anyone who does.

So to all manufacturers of roller furling jib systems—thank you!

Most of us cruising types are happy with a bottom-up furler, the kind you’ll see on most yachts. It's a simple, reliable system where the sail furls from the tack upwards. But on larger yachts, or for those who just appreciate the ultimate in convenience, electric or hydraulic systems are becoming more common. A pal of mine has an electric one of these on his beautiful Jeanneau 54DS. Imagine pressing a button and watching your sail furl or unfurl effortlessly; it dramatically reduces the physical effort required, making sailing safer and far more accessible, especially when you're single-handing or have a less experienced crew aboard.

Then there are the continuous line furlers, designed primarily for lightweight sails like Code Zeros or asymmetric spinnakers. Unlike traditional furlers, these use a closed loop, offering super smooth and rapid furling. It opens up a new dimension of sail handling for those who want to get a bit more speed out of their boat in light air without the hassle of a traditional dousing sock.

Getting to Grips With Maintenance

Proper maintenance is the key to ensuring your furling system works reliably when you need it most. My annual ritual, typically performed during my yacht's spring refit, involves a thorough inspection of the entire furling system.

- A simple rinse isn't enough. While a freshwater rinse is excellent for flushing out salt crystals, modern systems, particularly those with sealed bearings, need more specific attention.

- Check those bearings. You should inspect the furling drum and swivel for any signs of wear or damage. Many modern furlers have sealed bearings that require no lubrication, but some older or specific models might have grease points—always refer to your specific furler’s manual.

- Don't forget the forestay. This is critical. The furler is built around the forestay, and proper tension is vital for the system to operate smoothly and for the sail to set correctly. Too little tension can lead to sag, hindering both furling and sail shape.

- Keep an eye on the line. I've learned from experience that a frayed or stiff furling line is a disaster waiting to happen. Look out for subtle signs of wear on the furling line itself—fraying or stiffness means it’s time for a replacement before it becomes a problem at sea.

Tuning Your Rig & Sail for Optimal Performance

To get the most out of your headsail, you've got to understand how it works with the rest of your boat's rigging.

- The Luff Curve and Forestay Sag: Your sailmaker built a specific luff curve into your headsail to match the expected sag of your forestay. That sag—the sideways curve of the forestay under load—is designed to give the sail a powerful shape in light winds.

- Backstay Tension is Your Friend: On most masthead rigs, the backstay is your primary tool for controlling forestay sag. Tightening the backstay pulls the mast aft, which in turn increases the tension on the forestay. This reduces sag, flattening the headsail for better upwind performance and pointing ability in stronger winds. Conversely, easing the backstay allows the forestay to sag, making the headsail fuller and more powerful for light air sailing.

Reefing in Different Conditions

The way you use your furler should change with the wind and sea state.

Heavier Weather

Always err on the side of caution and reef early. A good rule of thumb is if you're consistently heeling more than 15-20 degrees or have a hard helm, it's time to reduce sail. The great advantage of a furler is you can do this from the cockpit. To make the process smoother, bear off the wind slightly to depower the headsail. Ease the sheet just enough to take the pressure off as you pull the furling line.

Lighter Air

In light air, you want to maximise sail area and power. Ensure your headsail is fully unfurled. This is where the subtle interplay of rig tuning comes in. By easing the backstay, you can increase the forestay sag, which creates a deeper, more powerful sail shape that will help you move in a light breeze.

But all this about adjusting backstay tension for various conditions won't mean much to most of us cruisers who don't have a fractional rig and a hydraulic or manual backstay adjuster. For us, we slacken the backstay off at the end of one season and tension it again at the beginning of the next. Well I do, anyway.

Avoiding Roller Reefing Foul-Ups

The most common problem I've encountered with furlers isn't equipment failure, but a simple set-up issue. I learnt this the hard way on a passage from Plymouth to Benodet (France) when the halyard twisted around the foil in a rising gale. It was a stressful experience and one I never want to repeat.

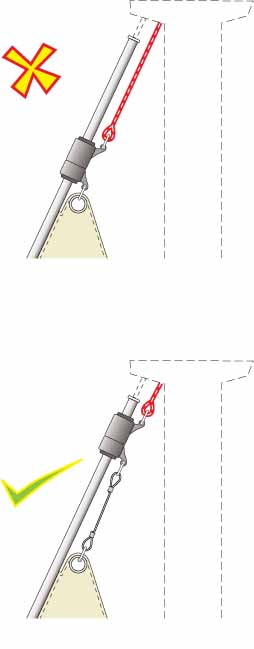

The problem: If the luff of your sail is much shorter than the foil, the halyard can—and according to Murphy’s Law, it will—get twisted around the foil, jamming up the works.

The solution: Prevention is simple. Fit a short wire strop between the top swivel and the head of the sail. Now the exposed length of the halyard is too short to wrap around the foil, and it'll prevent the top section of the swivel turning. Problem averted.

What if things go wrong that aren't a simple halyard wrap? If your furler becomes stiff or the sail doesn't furl smoothly, first check the halyard tension. Ensure the furling line is running freely through all fairleads and clutches, and that there are no kinks or twists. If the sail is reluctant to furl, try easing the sheet slightly as you pull the furling line; sometimes excessive sheet tension is the culprit.

Emergency Procedures

A jammed furler at sea can be a very serious situation. Here’s what you need to know:

- First, don't panic. Ease the mainsail or bear off the wind to reduce pressure on the rig.

- If the furler is jammed and you can't furl the sail, your best bet is to release the tack from the furler drum and drop the sail. It'll be messy and difficult, but it's the safest way to get the sail down.

- If you absolutely can't drop the sail, you can attempt the "maypole" method. Take one jib sheet off, coil the other, and motor the boat in tight circles while passing the coil around the forestay to force the sail to furl. This is a last-resort measure and is dangerous, but it can work.

- Always carry sharp cutters on deck to cut a sheet or halyard if it becomes jammed and you need to release the sail immediately.

Adjusting the Sheeting Angle

When you reef your headsail, the position of the jib sheet car on the track must also be adjusted. It's a geometry thing: the jib sheet must pull equally along the foot of the sail and the leech, or the sail's shape will be distorted.

Move the sheet car forward as the sail area decreases

Move the sheet car forward as the sail area decreasesYou can check if you've got the jib sheet car in the correct position by watching the tell-tales in the luff:

- If the upper tell-tales break before the lower ones, the jib sheet car is too far forward.

- If the lower tell-tales break before the upper ones, the jib sheet car is too far aft.

- When all tell-tales break at the same time, you've got the car in the right position.

You'll find that a sail with a higher clew, like a yankee on a cutter rig, will enable the headsail to be progressively rolled without you having to adjust the position of the car.

Whilst on the subject of cutters, my choice is not to have a roller furling gear on the staysail. If you stick with a hanked-on staysail, it can be easily replaced by a hanked-on storm jib when conditions demand it.

Other Headsail Considerations

Regardless of where you sail, a sacrificial UV strip on your headsail is essential to protect the sail from ultraviolet damage when it is fully furled. This strip of acrylic fabric is stitched to the leech and foot of the sail and protects the main body of the sail from the sun. Without it, the life of your sail will be drastically shortened.

Summing Up

For cruising sailors, the roller furling jib is a fantastic piece of kit that enhances safety and convenience. While it may not offer the ultimate performance of a hanked-on sail, the trade-off is more than worthwhile. By understanding the different types of furlers available, performing regular maintenance, and knowing how to troubleshoot common issues, you can ensure your system remains reliable and efficient for many years of happy sailing. For a deeper understanding of reducing sail area in any condition, see our comprehensive guide on Reefing a Sail: The Ultimate Guide to Control & Safety at Sea.

This article was written by Dick McClary, RYA Yachtmaster and author of the RYA publications 'Offshore Sailing' and 'Fishing Afloat', member of The Yachting Journalists Association (YJA), and erstwhile member of the Ocean Cruising Club (OCC).

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main benefit of a roller furling headsail?

What is the main benefit of a roller furling headsail?

he main benefit is the ability to adjust the sail area from the safety of the cockpit, which enhances both convenience and safety, particularly in challenging weather or when sailing with a limited crew.

Can I use a roller furler on any sailboat?

Can I use a roller furler on any sailboat?

Most modern sailboats can be fitted with a roller furling system. However, compatibility depends on the specific rig and mast configuration. It's best to consult a professional rigger.

How often should I inspect my furling system?

How often should I inspect my furling system?

An annual inspection of the furling drum, swivel, forestay tension, and furling line is recommended to check for wear and tear and ensure smooth operation.

What is a sacrificial UV strip?

What is a sacrificial UV strip?

A sacrificial UV strip is a protective layer of UV-resistant fabric sewn along the leech and foot of the headsail. It protects the sail from sun damage when it is furled.

Why do I need to adjust my jib sheet car when I reef my headsail?

Why do I need to adjust my jib sheet car when I reef my headsail?

Adjusting the jib sheet car is crucial to maintain the correct sheeting angle. This ensures the sail's shape remains efficient and balanced, preventing distortion that would reduce its drive.

Recent Articles

-

Moody 37 Review: Specs, Performance & Cruising Analysis

Jan 23, 26 04:46 AM

A comprehensive review of the Moody 37 sailboat. Explore technical specifications, design ratios, interior layout, and performance for blue water cruising. -

Sea Wolf 40 Review: Specs, Ratios & Cruising Performance Analysis

Jan 22, 26 04:13 AM

An expert review of the Sea Wolf 40. We analyse design ratios, construction quality, and blue-water cruising capabilities for prospective owners. -

Hunter Passage 42 Sailboat: Specs, Performance & Cruising Analysis

Jan 21, 26 09:34 AM

Explore the Hunter Passage 42 sailboat. Includes detailed design ratios, performance analysis, interior layout review, and expert cruising advice for owners.